It’s called Devastation Trail in Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park because lava swallowed the forest and charred the ground from green to black. In 1959, Kīlauea Iki erupted on Hawai‘i Island, and for 37 days, it spewed ash and sputtered fountains of lava, turning the hollow crater into a burning, molten lake.

Almost nothing survived, save for a handful of trees that were damaged but not destroyed, their trunks stripped of branches and leaves by falling cinder and spatter. They stand like skeletons, stark against the volcanic nothingness, white as bone. Other trees that were engulfed but not immediately burned left behind “lava trees”: upright, hollow trace fossils that resemble stone sculptures.

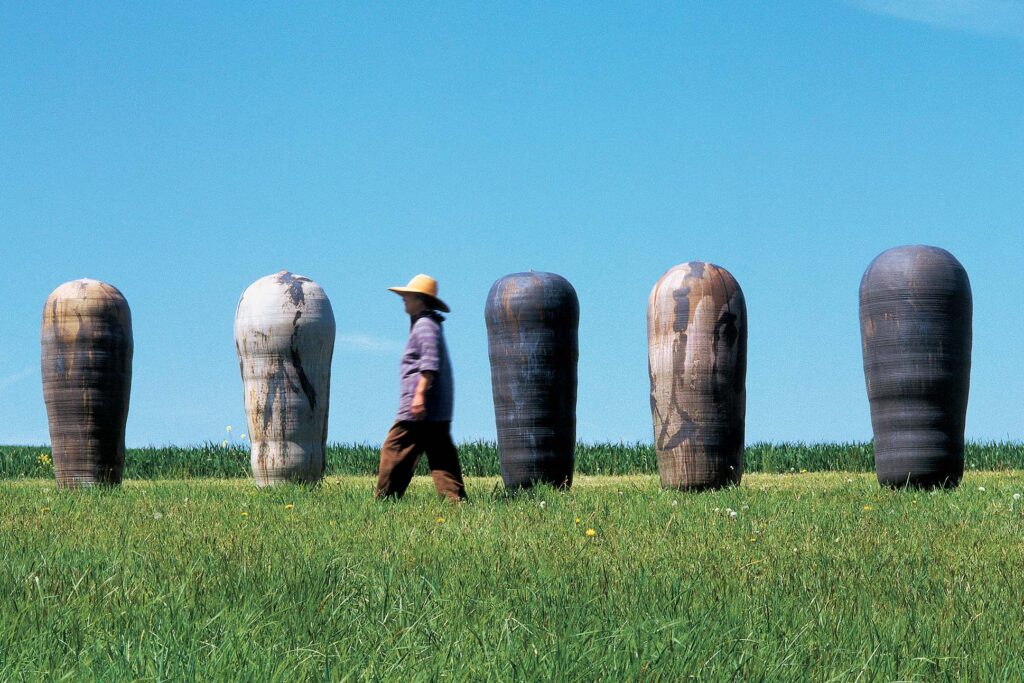

Starting in the 1970s, the ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu created her own Devastation Trail. Inspired by the roughly one-mile path of destruction, she began molding thick clay slabs into tall, hollow cylinders of up to eight or more feet tall. In Homage to Devastation Forest (Tree Man Forest), seven tree-like forms are clustered on a field of crushed rocks, glazed in striated tones of moon white, obsidian black, and soil brown. Another work, entitled Lava Forest, stands among the plant life in the front courtyard of Hilo International Airport, their phallic forms stained in inky black and ochre hues.

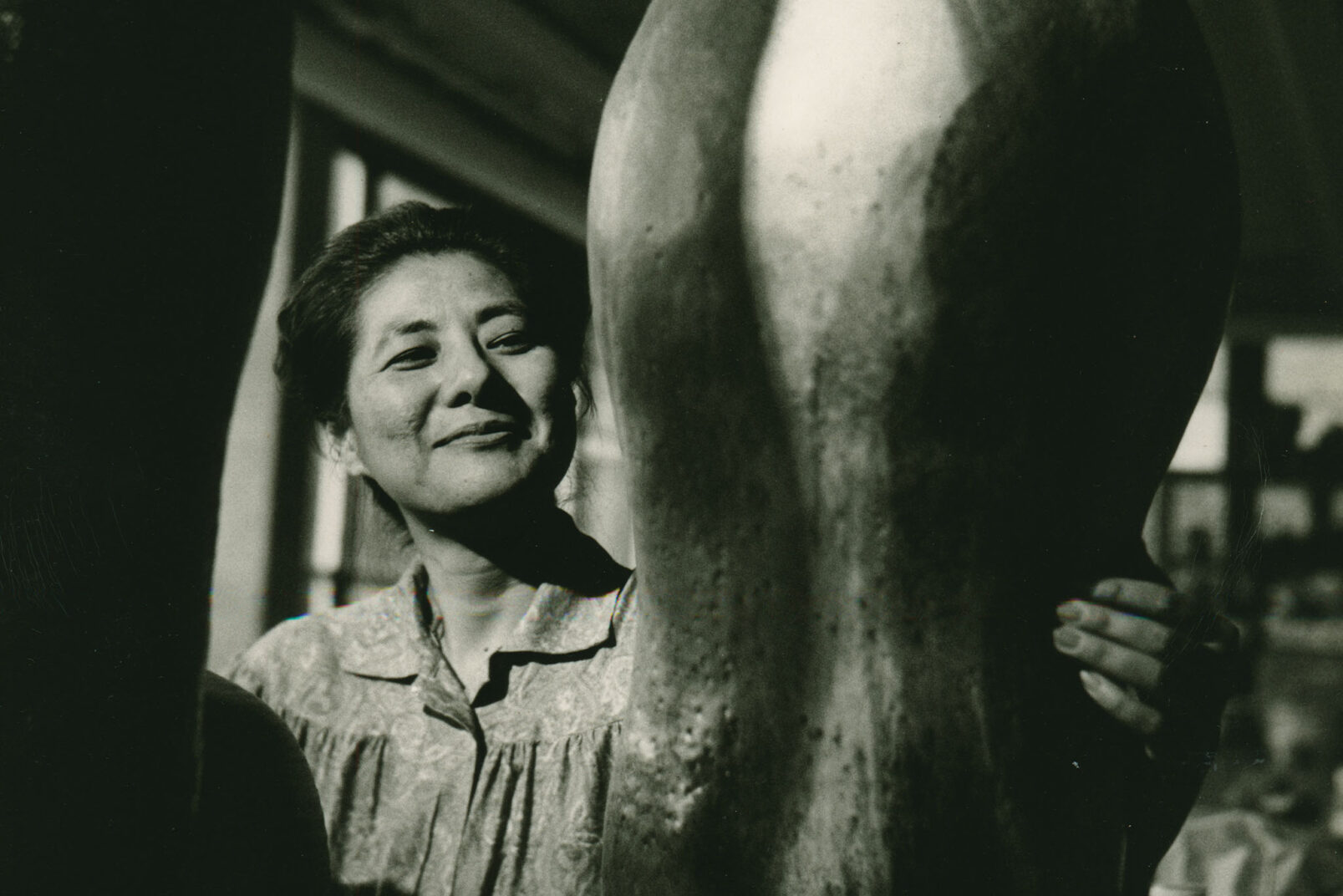

“It must be true that where you were born influences you,” Takaezu, born to Okinawan immigrant parents in 1922 in Pepe‘ekeo, Hawai‘i, told the Princeton Alumni Weekly in 1982. The impact that the islands had on Takaezu’s work is apparent throughout her oeuvre—either explicitly, as with her “Makaha Blue” works, which capture the vibrant color of the ocean on the west side of O‘ahu, or implicitly, in glazes of golden orange and soft pink that mimic the sunrise from the summit of Haleakalā on Maui.

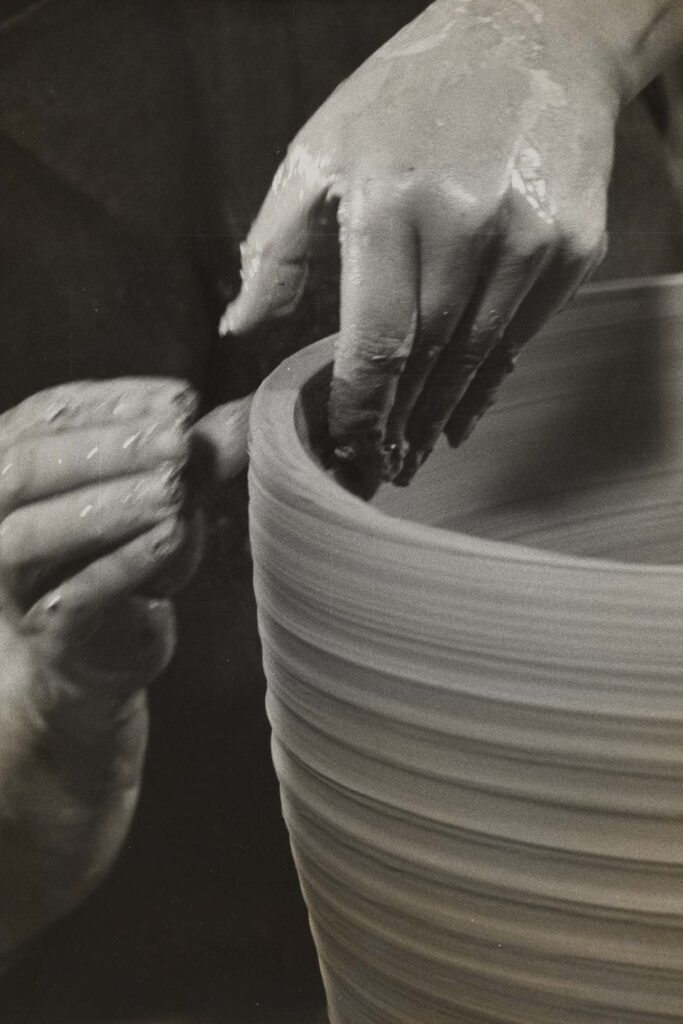

At 18, she moved from Maui (her family relocated there in 1931) to O‘ahu and found work as a housekeeper for Hugh and Lita Gantt of the Hawaiian Potters’ Guild. It was there that she met her lifelong mentor, Lieutenant Carl Massa, and honed pottery skills that later led her to the ceramics program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Takaezu would go on to enroll in drawing classes at the Honolulu School of Art; study ceramics, design, art history, and weaving at the university; and eventually leave the islands to study under renowned Finnish-American artist Maija Grotell at the prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Arts in Michigan.

“Hawai‘i was where I learned technique; Cranbrook was where I found myself,” Takaezu has said of her studies there. Grotell encouraged her self-discovery, stirring her to experiment with multi-spouted tea vessels and early iterations of the closed forms for which Takaezu would ultimately become known.

Despite her growing sense of individuality, Takaezu had long felt divided by her Okinawan heritage and American identity. According to Darlene Fukuji, Takaezu’s great-niece and president of the Toshiko Takaezu Foundation, there was a constant pressure to cast off one identity in favor of another: Okinawan for Japanese after the Ryukyu archipelago was annexed in 1879; Japanese for American during World War II. “It’s so complicated and also comes out really beautifully in her work, those dualities,” Fukuji says.

In 1959, Takaezu traveled to mainland Japan and Okinawa for eight months to commune with her origins and other ceramicists about the medium. There she met potter Tōyō Kaneshige who reintroduced her to Shōji Hamada, Sōetsu Yanagi, and other leaders of the mingei, or folk craft, movement, which focused on elevating ordinary forms like bowls into a higher art.

Takaezu was more drawn, however, to the work of Kazuo Yagi, the head of the avant-garde clay group Sōdeisha, or the “Crawling through Mud Association,” which was formed in opposition to the dominant ceramic style of mingei. Their work emphasized the sculptural over the functional, and their pieces lacked the holes or “mouths” that defined quotidian vases and pots.

Under the aesthetic influence of Sōdeisha, Takaezu returned to the states and created some of her most distinctive work, which continued to evolve beyond utilitarian cups, plates, and bowls to include ball-shaped “moon” pots and sculptural closed vessels that narrow into nipple-like points and contain ceramic “rattles”—bits of clay she would drop inside before closing the shape and kiln firing.

The closed form afforded Takaezu a wider canvas on which to explore color and play with glazes in an abstract-expressionist manner, giving her pieces their signature “paintings-in-the-round” quality. “I was able successfully to merge the glaze as painting to the form, so that the two—painting and form—became one total and complete piece,” the artist once said, according to the Toshiko Takaezu Foundation. “In some ways this form, and the painting on it, have returned me to sculpture and painting on canvas.”

Regarded by art-world figures of the time as the “Madonna of Clay” and “the most important female ceramicist in America,” Takaezu was pivotal in transforming the traditionally functional medium into fine art in the United States. She was named a Living Treasure of Hawai‘i in 1987 and received the Konjuhosho Award in 2010 by the emperor of Japan as someone who has made significant contributions to Japanese society—in part because she fully integrated herself into her art. “I felt like a ping-pong, back and forth,” Takaezu told interviewer Daniel Belgrad in 1993 in reference to her upbringing. “But then, when I got older, I realized that it isn’t East or West, really, it’s yourself. You take the best of both.”