Soaring in the wind over land and sea, traditional Native Hawaiian kites, or lupe, once dotted the sky in many shapes and sizes. Not only were kites used for recreation, but they were also tools for fishing, weather forecasting, and sporting competitions. The practice, famously mastered by the legendary demigod Maui, nearly disappeared following the arrival of Westerners in the islands, but a handful of contemporary artists are rekindling interest in the art of ho‘olele lupe, or kite-making.

“It’s been something I’ve wanted to do for a really long time because the primary material that kites are made out of is kapa,” says Lehuauakea, a Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) kapa maker who was raised on Hawai‘i Island and now lives in New Mexico. Though mentions of them abound in Hawaiian mo‘olelo (stories) and ‘ōlelo no‘eau (proverbs), Lehuauakea says, “We don’t have Native Hawaiian kite specimens that have survived, to our knowledge.”

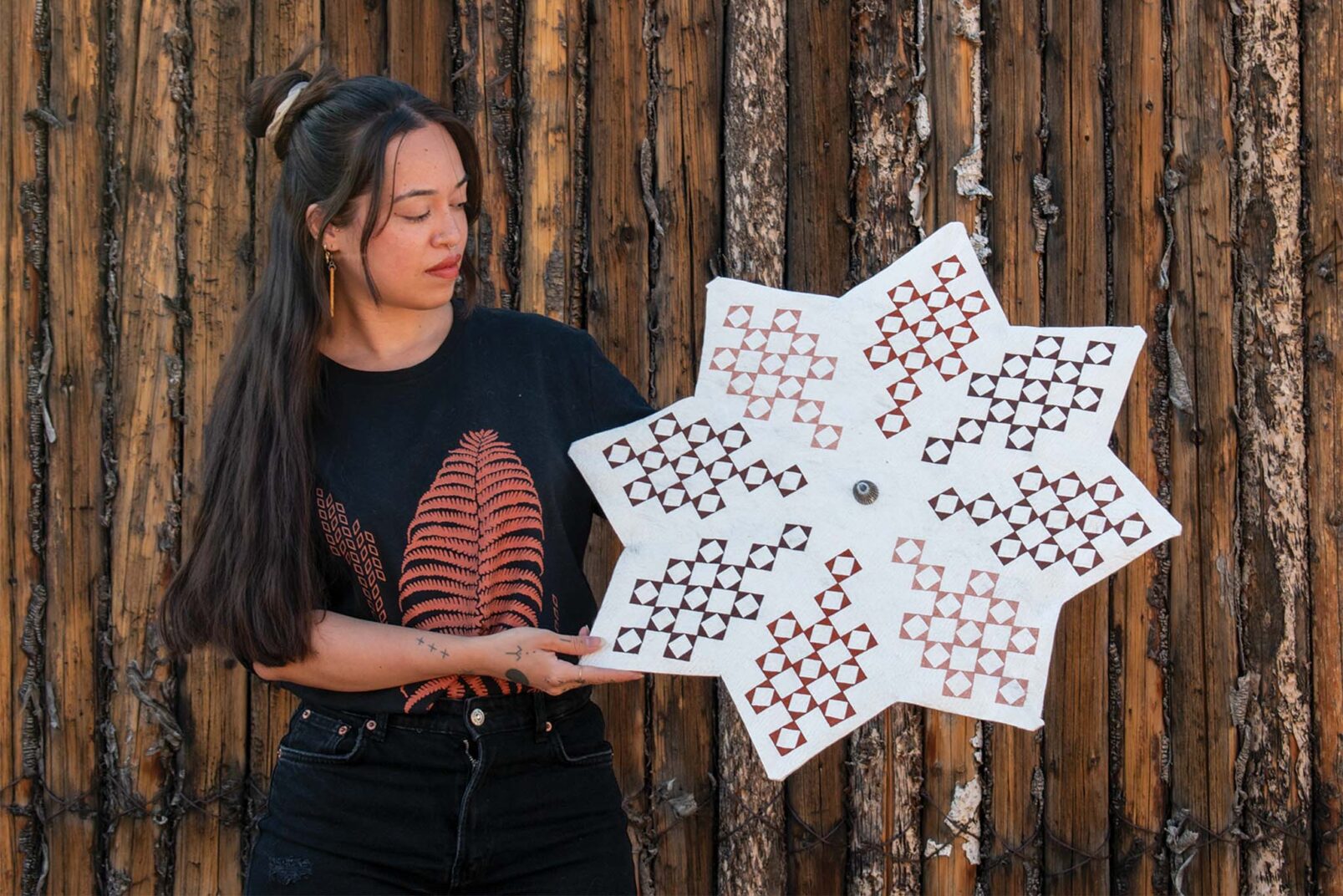

As part of a grant from the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, Lehuauakea began extensively researching traditional kites from around the Pacific—how they were constructed, what materials were used, and how they were lashed together. After some trial and error, Lehuauakea recreated six traditional Native Hawaiian kites using a mix of hau (hibiscus) branches and ‘ohe (bamboo) for the frame, kapa for the sail, and hau bark as cordage. Two of Lehuauakea’s kites are currently on display at the Robert C. Williams Museum of Papermaking in Atlanta, Georgia, and more will be exhibited at Central Washington University in October.

Lupe were used not only for recreation but as tools for fishing, weather forecasting, and sporting competitions.

Traditionally, Hawaiian kites are named for their diverse shapes, such as the lupe lā (round sun kite), lupe hōkū (star kite), lupe hīhīmanu (manta ray kite), and lupe mahina (crescent moon kite). Once built, Lehuauakea chooses a pattern for each kite and applies it with sustainably sourced dye materials and paints. “It’s kind of a mix between what is available in my pigment collection, which is pretty vast,” Lehuauakea says, citing as inspiration both personal preference and colors that signify specific Hawaiian deities alluded to in the kite’s motifs.

Chucky Boy Chock, director of the Kaua‘i Museum, grew up playing with Hawaiian kites that were made out of newspaper. He was exposed to the Hawaiian cultural practice of flying kites through his grandfather, Papa David Nalehua Kahaku, who was born in the early 1900s and learned the art of ho‘olele lupe from his elders. Highly in tune with the natural world, Chock’s grandfather would fly a kite to help him predict when fish would be plentiful. “The certain wind told him that the kalepa rain is coming,” Chock says. “So when the rain comes, he knows the nehu (Hawaiian anchovy) will be running all over He‘eia and Kāne‘ohe Bay.”

Chock recalls one traditional kapa kite that was cherished by the family, especially Chock’s grandma. “I never did fly tūtū’s one, though, because he did not allow it. That was kapu (forbidden),” Chock says. “My favorite, really, was the lupe manu (bird kite).”

When Lehuauakea was creating kites for the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation grant project, Lehuauakea’s partner, Kanaka Maoli hand-cut paper artist Ian Kuali‘i, crafted additional kites using the leftover materials. Inspired by a petroglyph on Hawai‘i Island, Kuali‘i constructed a giant lupe manu that spans 5 feet by 2.5 inches across and 4 feet by 41 inches from head to tail. “The hardest part was trying to figure out the stretching and tension of the kapa skin,” Kuali‘i says. “But overall, I’m just really proud to have completed it.” He doesn’t have plans to exhibit the kite, he says, explaining that he only wants the kites to be used for cultural purposes.

Though the grant period has ended, Lehuauakea and Kuali‘i both say that they will continue making more kites in the future. “As a kapa maker,” Lehuauakea says, “I think it’s something that will keep coming up in my work.”