Kirk Kurokawa, painter

From Pū‘ali Komohana, Wailuku

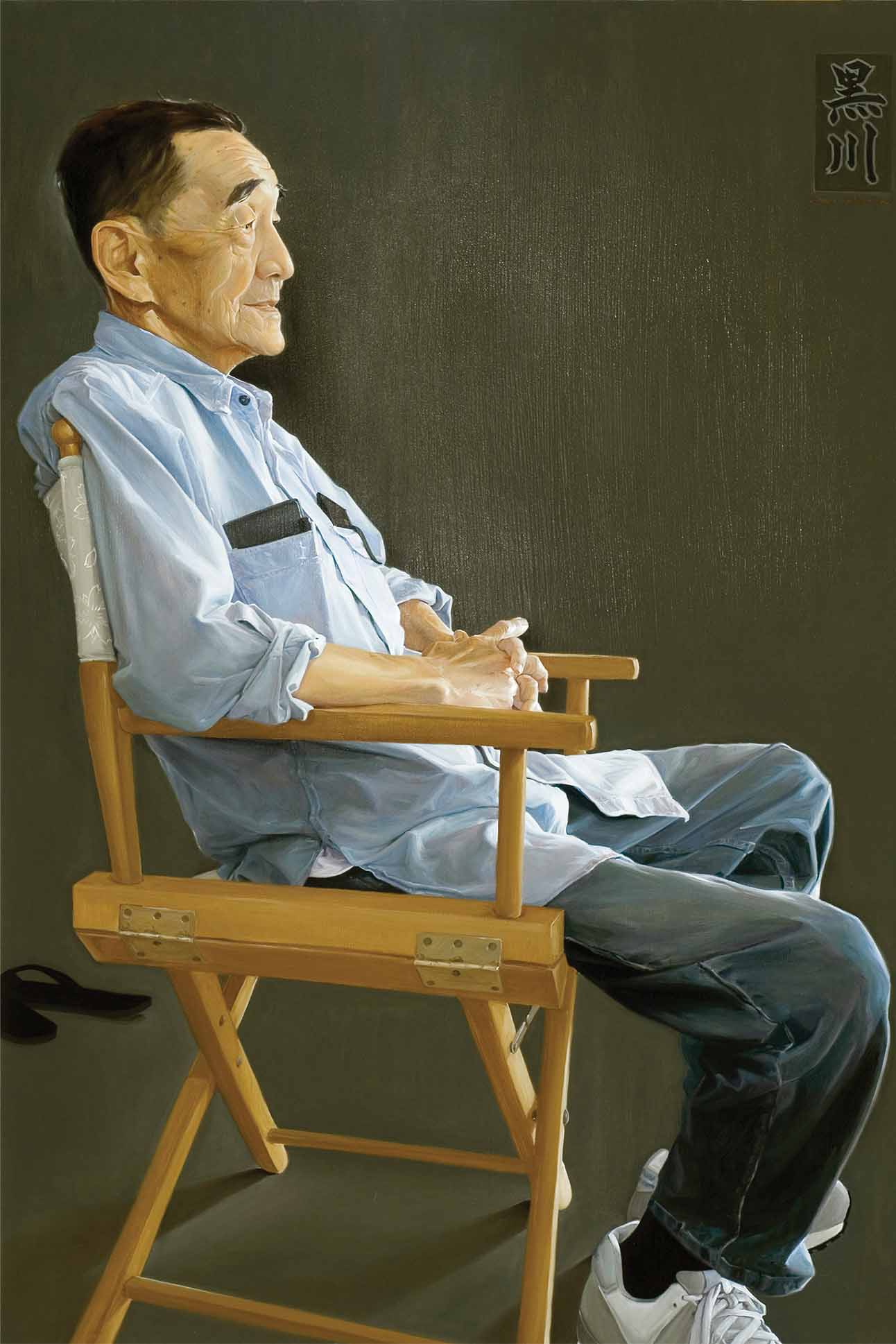

In 2006, Maui native Kirk Kurokawa entered the Schaefer Portrait Challenge, a statewide juried exhibition held at Maui Arts and Cultural Center, and won the Juror’s Choice Award for “The Real McCoy,” a life-size portrait of local artist—and Kurokawa’s personal hero—Tadashi Sato. Though Sato passed away during Kurokawa’s rendering, the experience continues to influence his work today. “At his house in Lahaina, I spent hours just listening to his words of wisdom,” Kurokawa says. “The painting launched my career, but the time I spent with Tadashi was a pivotal moment for me.”

Working mostly from his own photographs, Kurokawa uses oil paint on wood or canvas to capture everyday life in Maui, usually centered on a single figure. After the Lahaina fires, Kurokawa painted “Persevere,” featuring a papier-mâché daruma, a traditional Japanese wishing doll. Weighted at the bottom, the daruma embodies the spirit of Maui’s people through the Japanese concept of nanakorobi yaoki, which translates to “fall seven times, stand up eight.”

One of Kurokawa’s favorite subjects is endangered Hawaiian birds, such as the ‘amakihi (Hawaiian honeycreeper) and the kiwikiu (Maui parrotbill). “The birds represent a lot of things in Hawai‘i that are going away,” he says. “If we really put our minds to it, we could do much better and save these things that we love so much—whether it’s our birds, our water, or our land.”

In “Allstar,” Kurokawa showcases his dad, Reggie, with arms crossed and a cigar hanging from his mouth. Sitting at Reggie’s feet is his longtime companion, a Pomeranian named ‘Ele‘ele, sporting a cross-shaped omamori, or Japanese good-luck charm, on his collar. “People think he’s a tough guy, but if you start talking about his grandkids, he’s in tears,” Kurokawa says. “My dad is all Maui … one of those guys who will do anything for anybody.”

Enoka O La‘i Phillips, lei hulu

From Lahaina, Paunau

During Hawaiian immersion studies at Lahainaluna High School, Enoka Phillips was mesmerized by images of ‘ahu ‘ula (feather capes), mahiole (feather helmets), kāhili (feather staffs), and lei hulu (feather lei). The intricate nature and vivid colors of the traditional Hawaiian featherwork donned by high-ranking chiefs as symbols of divinity and spiritual protection stirred something primal in him, and he sought out mentors in the craft.

In early 2018, Phillips began fashioning lei hulu and lei humupapa (hat bands) under master featherwork artisans Florence Makekau, Susie Uwēko‘olani, and Pattie Gomez, who were well-known in the Maui community for their art and aloha. “Aunty Flo never denied anyone who wanted to learn, and she made me promise to pass along the ‘ike (knowledge) to others,” Phillips says. About six months into his featherwork journey, Phillips discovered that his great-grandmother, Libbie Kaiwi Hokoana, had been a prolific lei hulu artisan. “I knew at that moment that I was on the right track, and it was my kuleana (responsibility) to continue the art form,” he adds.

Crafted with thousands of pheasant, peacock, goose, seabird, and other ethically sourced feathers, the lei hulu and lei humupapa that Phillips creates often incorporate vibrant hues of yellow, orange, and red as a tribute to Maui’s greatest resource. “For Hawaiians, Kanehoalani (the sun) was the origin of everything—energy, light, even water,” he says. “When I give a lei hulu to someone, I want them to feel that sense of warmth and radiant beauty.”

At age 21, Phillips was invited to serve as a kumu (teacher) at Kauluhiwaolele, the fiber arts conference at Kā‘anapali Beach Hotel, an event he had attended many times as a student. “I questioned whether or not I was ready to stand alongside these legendary kumu and artisans who have been practicing and perfecting their craft for decades,” he recalls. “Then I remembered Aunty Flo’s special request and realized maybe I’m right where I’m supposed to be.”

Abigail Kahilikia Romanchak, printmaker

From Kula, Kēōkea

Seeking to preserve the delicate and disrupted ecosystem on her home island of Maui, and to perpetuate Native Hawaiian traditions by placing them in a contemporary context, Abigail Romanchak’s enigmatic prints are as much calls-to-action as they are works of art. In works such as “He Hō‘ike no ke Ola,” a reflection on marine food chain collapse, the artist transforms data points into deftly layered imagery to assert a Hawaiian sense of identity and culture while conveying the gravity of human impacts on the natural environment.

Following the devastating fires in Lahaina, Romanchak created “Pilina” to honor the moku, or traditional land divisions, of pre-contact Hawai‘i. In 2024, she exhibited the work in 8×8: Source, a group show at the Shangri La Museum of Islamic Art, Culture & Design in Honolulu, where it beckons viewers to contemplate the vital role of wai (water) and the Indigenous resource-management practices necessary to protect the land and its people.

A longtime practitioner of kapa-making, the Native Hawaiian tradition of pounding cloth from wauke (paper mulberry) tree bark, Romanchak often weaves fine details of the process into her art. According to Romanchak, the resulting embossed marks created from the kapa beater’s impact upon wet wauke are both subtle and significant. “When you hold them up to the light, they come to life and they tell a whole story,” she says.

As part of ‘Ae Kai: A Culture Lab on Convergence, an ongoing installment of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, Romanchak presented a large collagraph print series featuring spectrograms, or three-dimensional visualizations, of bird songs. In “Kāhea,” the artist pleads to hear the voices of the kiwikiu and ‘ākohekohe (crested honeycreeper) once again. In “Kani Le‘a,” the unique song of each currently endangered Hawaiian forest bird is represented, while bare sections of black represent the resounding silence of those species forever lost to extinction.

“Reminiscent of the lines and subtle layers embedded in the watermark of traditional kapa, which often recalled scenes in nature, I like to take the data and imagery and make it somewhat hidden,” Romanchak explains. “Viewers of my bird spectrogram prints might simply see a mess of squiggly black lines, until they slow down and work a little bit harder.”