In the darkened hall of Kennedy Theatre, the steady beat of taiko drums and the twang of a three-string shamisen echo through the air. As the stage curtains part, characters from the popular kabuki play The Maiden Benten and the Bandits of the White Waves spring into action, flowing freely between speech and precise movement.

“Everybody has to be moving, thinking, and acting in sync with each other,” says Julie Anne Iezzi, a professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Department of Theatre and Dance. Iezzi has taught kabuki, a stylized form of Japanese drama, for the last 25 years. She describes the collective, concerted effort within a performance as a vital “oneness.” “I talk about it as breathing together,” she says.

Kabuki’s origins are thought to date back to 1603, when Izumo no Okuni, a Japanese entertainer and shrine maiden, performed parodies of Buddhist prayers along the dry riverbed of Kyoto’s Kamo River. Okuni and her all-female troupe of outcasts and misfits delighted the working-class crowds with unique, dance-like spectacles. In Japanese, the word kabuki is comprised of three characters: “ka” for song, “bu” for dance, and “ki” for skill. When used as a verb, the word can mean “to lean in a certain direction,” and the term itself can also mean “bizarre” and “out of the ordinary.” All these etymologies combined, Iezzi notes, are perhaps a nod to the avant-garde nature of Okuni’s innovative style.

Hawai‘i’s own connection to kabuki developed during the late 19th century. As waves of Japanese immigrants arrived in the islands to work on sugar and pineapple plantations, they brought with them their cultural traditions, practices, and entertainment. As the children of these immigrants integrated into local academic institutions, Japanese language and heritage courses soon found a place in the curricula of local schools.

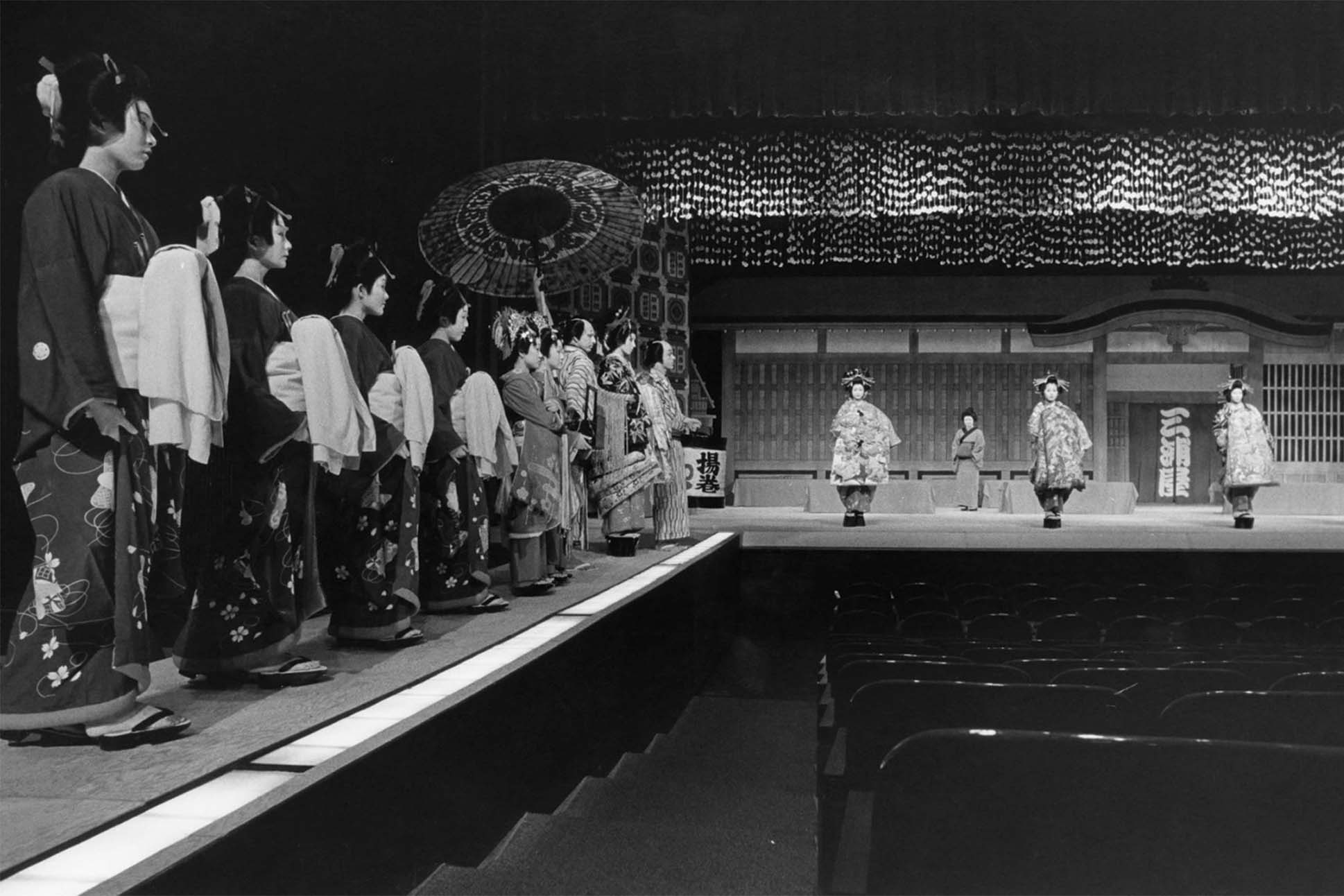

In 1924, the University of Hawai‘i’s student drama club presented its first kabuki play, Kawatake Mokuami’s five-act The Maiden Benten and the Bandits of the White Waves, commonly known as Benten Kozō, an exciting tale of disguised identities based on a true story of five thieves in Osaka during the Edo period. It was the first documented kabuki performance in the islands and was performed in English to make it accessible to non-Japanese speakers. One hundred years later, to honor the university’s 1924 kabuki performance, in conjunction with the theater’s 60th anniversary, Iezzi decided to bring three acts of the seminal play back to UH for 2024.

Preparing for The Maiden Benten and the Bandits of the White Waves was a physical, intellectual, and emotional endeavor. Rehearsals began in the fall with the cast and crew working several hours a day, six days a week. The theater department also invited kabuki master artists Monnosuke Ichikawa VIII and his two apprentices, Utaki Ichikawa and Takishō Ichikawa, to train the actors and ensure that their performances were true to form.

For Isabella O’Keeffe, a Master of Fine Arts candidate who played Nango Rikimaru, one of the production’s lead bandits, the opportunity to work with a kabuki master brought valuable lessons for both the stage and beyond. “Monnosuke said, ‘One of the worst things you can do is to forget and to go backwards,’” O’Keeffe says. “As long as you keep moving forward, it’s progress.”

For Kennedy Theatre technical director Justin Fragiao, learning about the relationship between individual expression and kabuki’s stringent form and framework was intriguing. “It’s not that there is no freedom, it’s just understanding that there are certain ways to do things,” Fragiao says, describing how even a simple gesture such as a hand wave conveys tremendous meaning, especially to those familiar with the genre. “It’s about finding that balance between making sure it reads correctly.”

Following their five sold-out performances on O‘ahu, the cast then took the show on the road to Japan by invitation from government officials in Gifu City, a region known for its kabuki heritage. Performances were held at Gifu Seiryū Bunka Plaza as well as the historic Aioi-za Theater. The tour marked a full-circle moment: Following the 100-year celebration of Hawai‘i’s first English-language kabuki production, the institution was now sharing The Maiden Benten and the Bandits of the White Waves in English with a native Japanese audience. At the culmination of each performance, Iezzi recalls the sense of pride and validation she and the cast felt upon seeing the number of paper-bundled coins that rained down upon the stage, a traditional gesture of approval in Japanese theater.

Now back in Hawai‘i, Iezzi is preparing for the upcoming semester at UH, where she hopes to continue impressing upon her students kabuki’s complexity as both a dance and a discipline. Whether in its translation, movements, or vocal intonations, practitioners eventually discover that the beauty of kabuki lies in the inability to master the art form. Students must strive for incremental improvement, knowing that the process itself is an ongoing lesson. “Within kabuki, there is never a sense of reaching perfection,” Iezzi says. “You can be in the field for 60 years and yet you are still learning.”