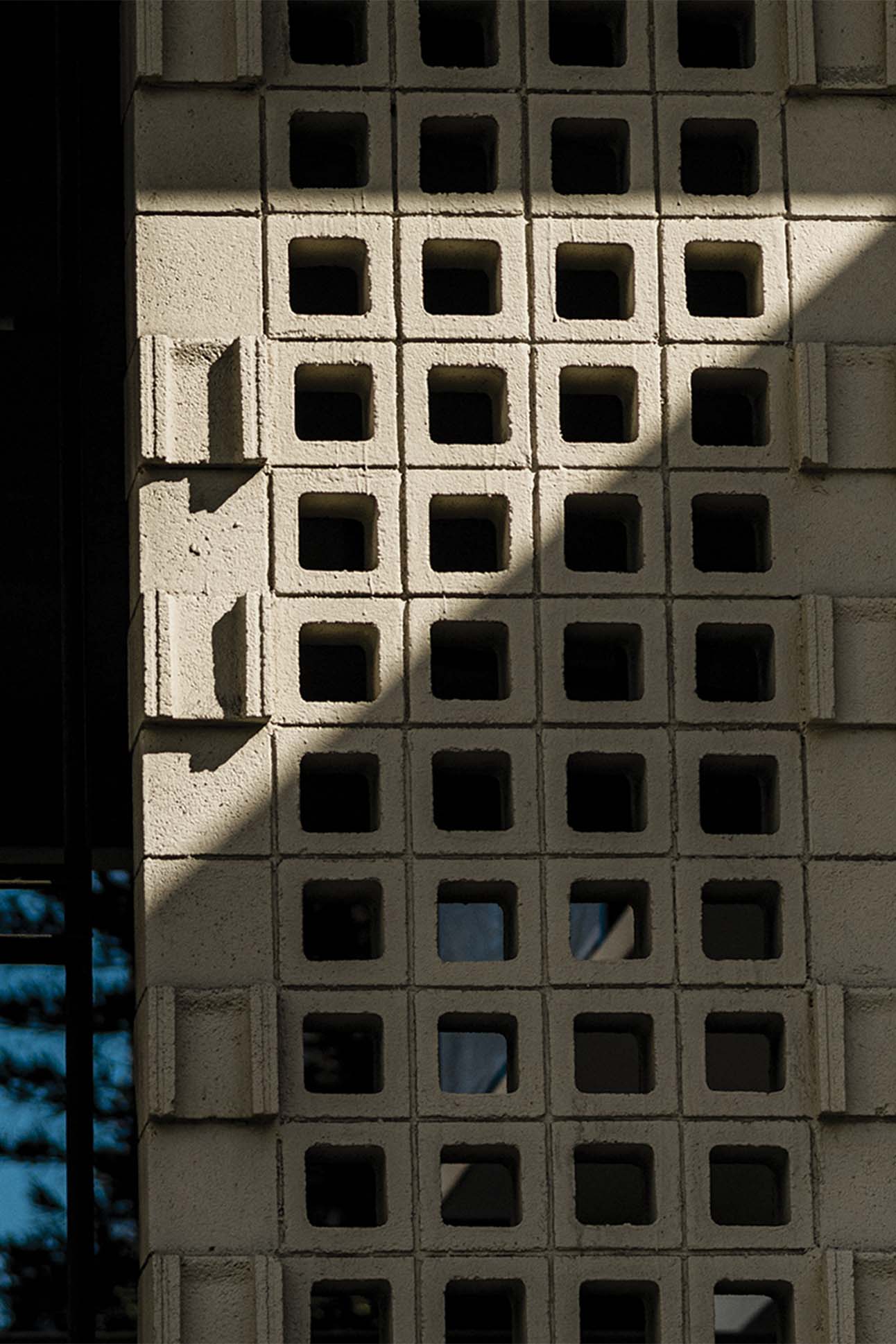

Ten years ago, when I first began exploring the neighborhoods around my wife’s and my apartment along the Ala Wai Canal, I kept noticing the same architectural detail over and over: small, hollow concrete blocks, typically with some sort of shape or pattern in the middle, like snowflakes children cut out of paper. Entire walls were made of them, the repetition of dozens, even hundreds, of blocks stacked on top of one another creating an even larger, more intricate pattern. The effect was an architecture that felt both solid and porous, sturdy and fragile. I was mesmerized.

I snapped a photo and posted it on Instagram, wondering if there was a technical term for this detail. It was local curator and community developer Wei Fang, then of Interisland Terminal, now of Arts and Letters Nu‘uanu, who eventually supplied the answer. She wrote one word: #breezeblocks.

Breezeblock hit the mainstream in the late 1950s. Enabled by advancements in concrete fabrication and rises in the costs of labor and traditional building materials like stone, breezeblock became a cost-effective way to screen buildings from excessive sun while also encouraging natural ventilation, making it particularly popular in hot and humid climates, like those of Hong Kong, Miami, and Honolulu. A concrete breezeblock wall had the added advantage of high thermal mass, meaning it absorbed the sun’s heat during the day and released it at night, making it well-suited to desert locales like Palm Springs. Like Islamic mashrabiya, breezeblock is an example of geographically influenced, climate-responsive architecture, a chunkier, more modern version of European brise-soleil or Indian jali.

Breezeblock was also cheap to produce. Thousands of blocks could be made with a single mold —“Play-Doh Fun Factory-style,” explains architect Jason Selley of Workshop-HI. Concrete masonry companies began offering standard shapes and patterns, which architects could select from catalogs.

The 1960s and ’70s saw a proliferation of decorative breezeblock screens, perhaps nowhere as noticeably as Honolulu, then in the middle of its post-statehood building boom. Although breezeblock has recently been nudged back into popularity thanks to a broader appreciation for midcentury modernism, it still doesn’t get the love it deserves, says architect Lance Walters. “Even though it is having a moment,” he says, “I think it’s still under-appreciated.”

Breezeblock invited modern architects to play. A single block could be flipped around or turned upside down to create new patterns. It was a totally new way to decorate façades, and yet there was something old-fashioned about it—almost reminiscent of making shapes and stacking blocks in childhood.

Today you’re as likely to find breezeblock on the sun-baked streets of suburban Pālolo Valley as you are on the shady sidewalks of Waikīkī’s Gold Coast. That’s because breezeblock historically offered architects customizability at almost no extra cost, making it particularly appealing on projects with modest budgets. In Honolulu, “there’s a lot of cookie-cutter, plantation-type homes,” Selley says. A home’s breezeblock pattern was the “one area where architects could flex some creativity within a standard module.”

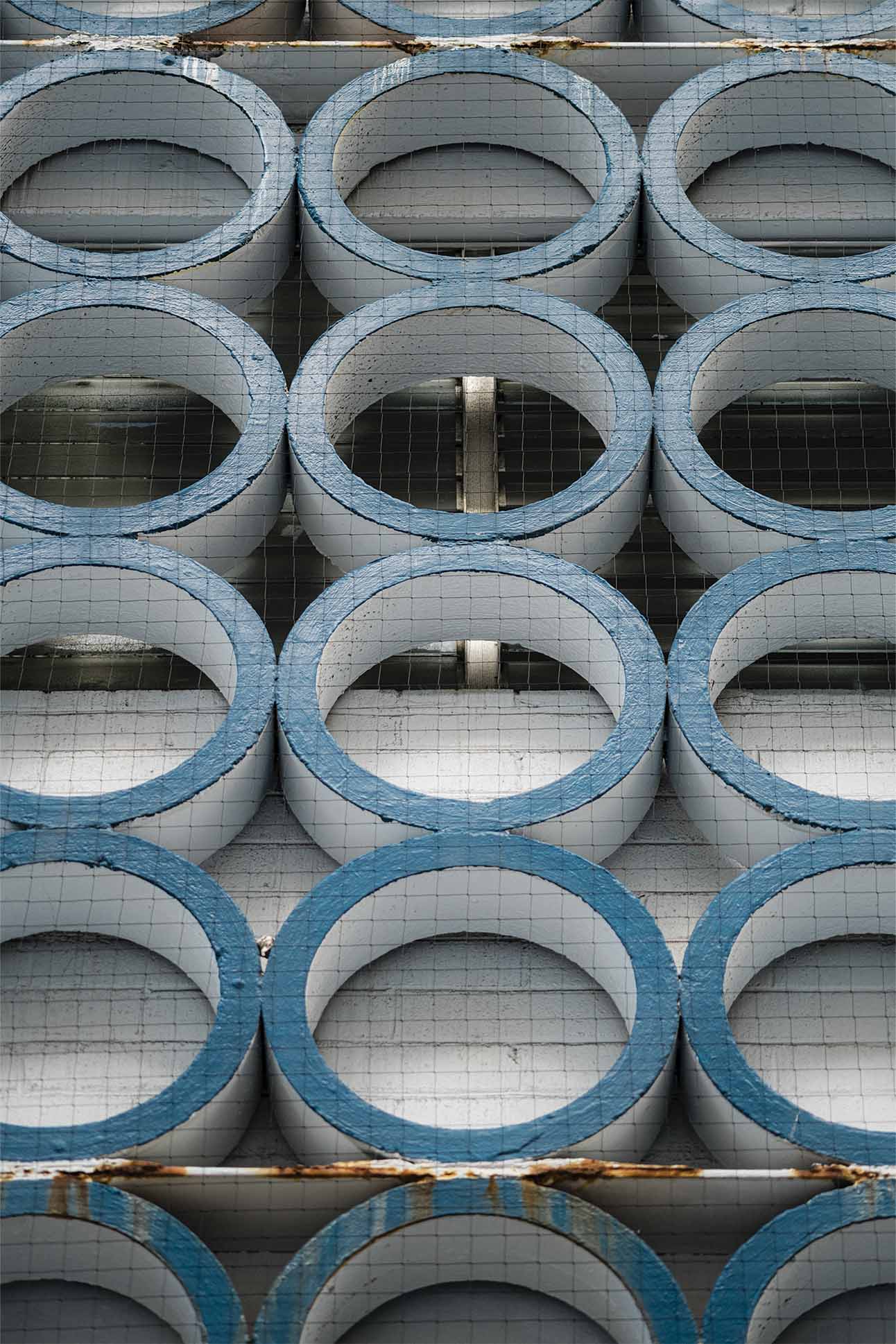

Breezeblock’s growing popularity may owe something to social media. Architecture critic Alexandra Lange has written that the life-inside-a-thumbnail experience of Instagram rewards particular modes of presenting architecture: “Grids, shadows against a wall, baby [Andreas] Gurskys of the repetitive commercial landscape.” What architectural element is more perfectly suited to that format than breezeblock? Beautiful grids inside of beautiful grids, each neatly obscuring what’s behind them.

Today, the artifacts of that period are omnipresent. Breezeblock can be found throughout Hawai‘i, in houses, hotels, banks, and bowling alleys, but is also seeing a resurgence in contemporary architecture. For the Kaimukī restaurant Mud Hen Water, Selley clad the base of the bar with a rectangular block that, when counterpoised, forms an abstract pattern of circles and intersecting lines. “We thought it’d be a fun juxtaposition, having the old-school breezeblock with a really beautiful white marble top on it,” Selley says.

If breezeblock is experiencing a kind of low-level renaissance in Hawai‘i, a big part of why is that it is humble, democratic, unfussy. Amid ever-more-inaccessible all-glass towers and an increasingly virtual world, concrete blocks are tactile and refreshingly solid. An echo of the past, it speaks to our desire for continuity in the midst of change, for signs and symbols that say to us, You belong here.