The new headquarters of the Hawai‘i Hochi strikes me as distinctly Japanese: the acute angles of the exterior, the spotless glass doors and floors inside, everything in its right place. It’s as if a Tokyo newsroom was airdropped into an industrial part of Kalihi near the airport, under the shadow of the freeway and the Honolulu rail. All of the staff at Hawai‘i’s only Japanese-language weekday newspaper are hard at work, and it’s quiet enough to hear the hum of the central air conditioning.

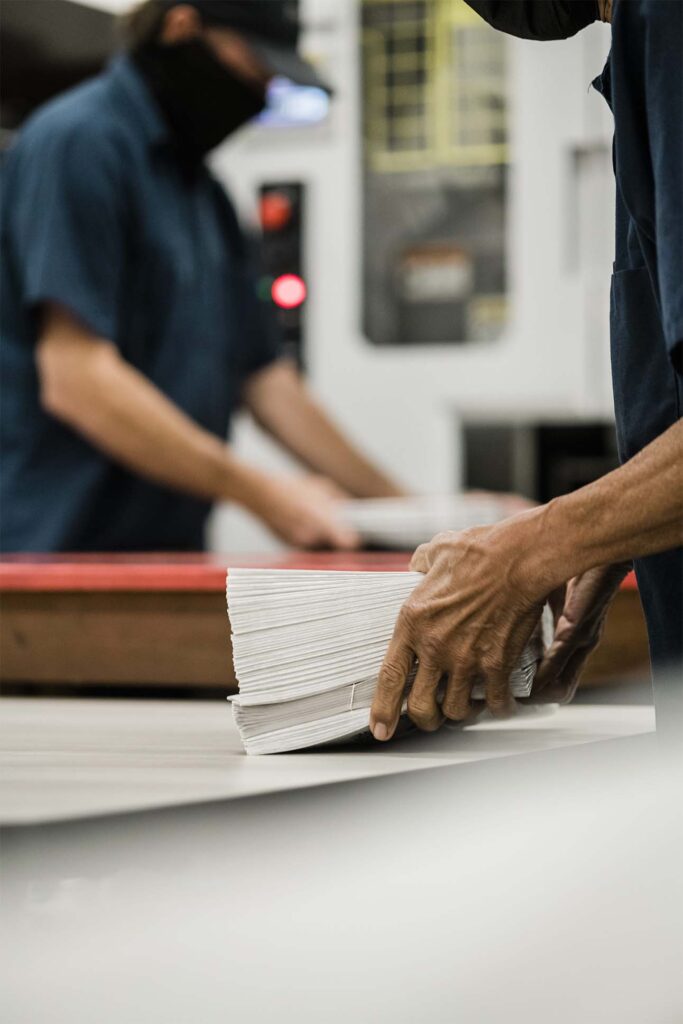

On the day of my visit, the Hawai‘i Hochi is covering the summer’s local bon dance celebrations, Tokyo’s Covid-19 numbers, and primary elections across the state. Politics, both in Hawai‘i and in Japan, are the paper’s forte. The Hawai‘i Hochi’s editor, Noriyoshi Kanaizumi, is in the middle of his workday, which begins at 4 a.m. and ends around 4 p.m. He works until midday on a shared document, converts it to a PDF, and walks a thumb drive down the hall to a desktop computer that sits between two steel rows of printers. The paper is printed in 15 minutes and then sent off to a distribution center on the west side of the island in time for the next day’s delivery.

The Hawai‘i Hochi is distributed to some 2,500 recipients, mostly on O‘ahu, and draws about as many readers online. “We’re a link between an older generation and a younger one,” says Grant Murata, the paper’s advertising and promotions manager, who explains that many of the Hawai‘i Hochi’s older readers grew up with the paper. Newer readers tend to be recent immigrants from Japan.

But like many newspapers, subscriptions are dwindling. “Our readership is declining in part because people pass away,” says president Taro Yoshida, who has the unenviable task of keeping the evolving business model of the daily paper profitable in the 21st century. “But for now, we have no plan to wrap up our paper copies. Our die-hard readers … have to get a hard copy in the mail.”

The paper is divided into three sections: Hawai‘i news reported in Japanese, Japanese news reported in Japanese, and Japanese news reported in English. “Local news always first,” Kanaizumi says.

A recent event at the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai‘i honored the paper’s first editor, Fred Kinzaburo Makino, who helped build a community around the local Japanese experience at the turn of the last century. Born the son of a Japanese mother and English trader in 1877 in Yokohama, Japan, he was fluent in both Japanese and English. He emigrated in 1899 and, after working in the plantations, opened Makino Drug Store in 1901.

He founded the Zokyu Kisei Kai, or the Higher Wage Association, with his brother and other community members, including Yasutaro Soga, editor of the Nippu Jiji, then the largest Japanese-language newspaper in the islands. They were imprisoned in 1909 for their activities in labor organizing.

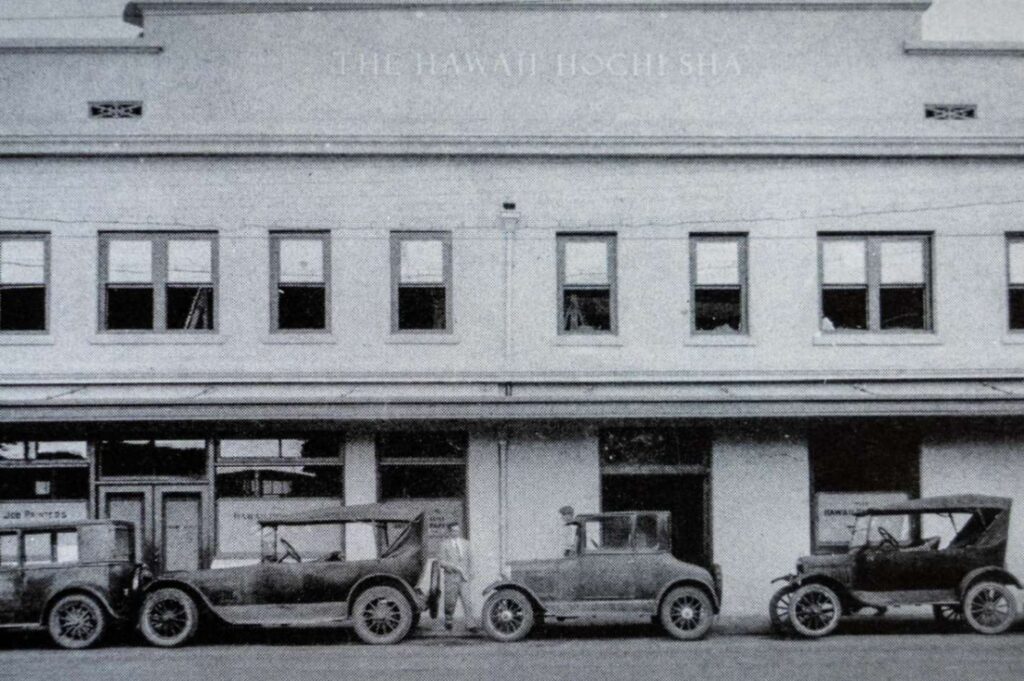

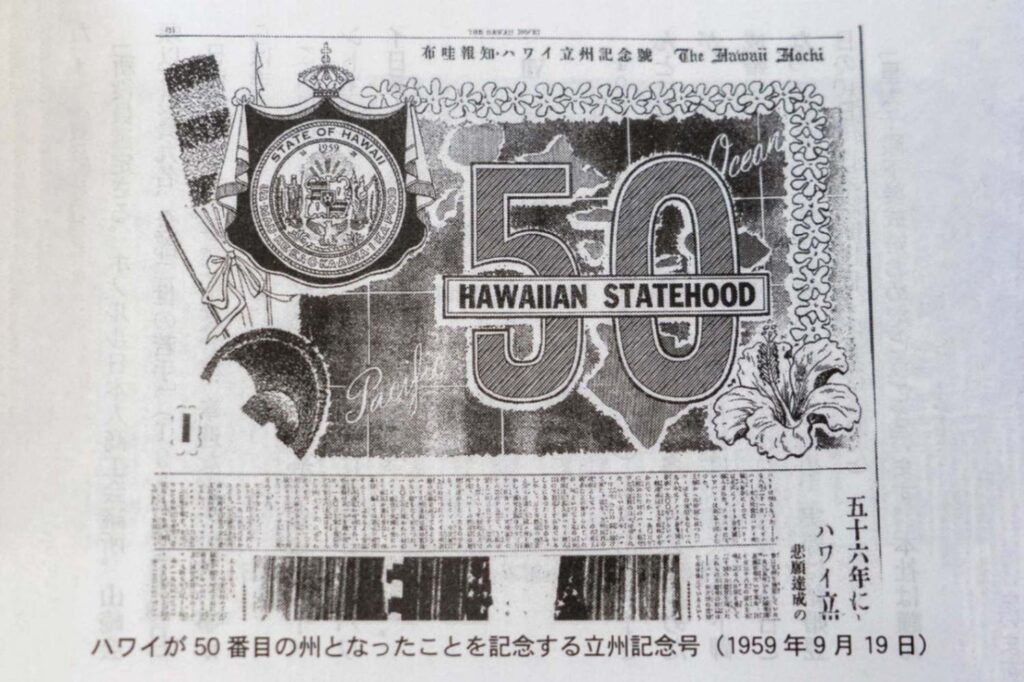

Founded to be the voice of Japanese workers in Hawai‘i, the Hawai‘i Hochi began publication in 1912, covering Japanese language in schools, the fight for citizenship, labor disputes, and sensational stories like the Massie case of 1932. During World War II, when the military government shuttered many local Japanese-language newspapers, the Hawai‘i Hochi persevered despite heavy censorship. It was a pivotal era for Japanese in Hawai‘i, who organized around racial discrimination, formed labor movements on sugar plantations, fought valiantly in the war, and entered professional life. The paper reported on it all. When Makino passed away in 1953, the community he reported on had become a powerful ethnic group in the islands.

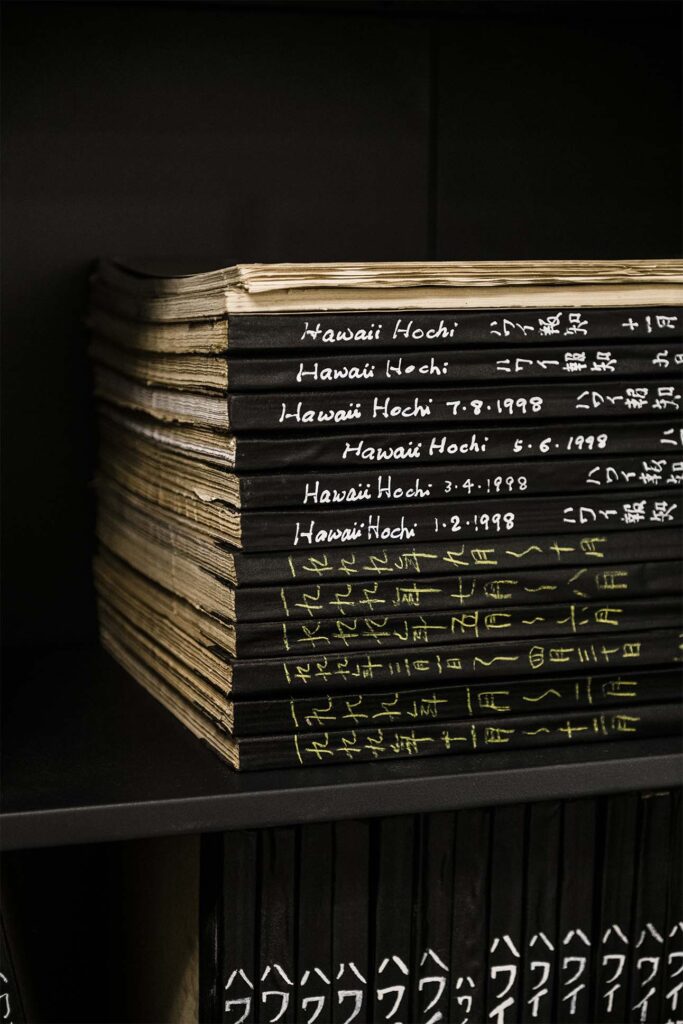

The editors open a steel file cabinet and pull out a book containing news articles published by the Hawai‘i Hochi in the summer of 1978. The average annual income of a local resident was a little over $10,000. The conversion of the yen to the dollar was 201 to 1. Gas prices were high. A primary election campaign was underway across the islands. July 5 saw the beginning of the Hawai‘i State Constitutional Convention, which enshrined in law many of the fiery issues of Indigenous advocacy, multi-ethnic democracy, and environmental protection advocated by the local Japanese community and the Hawaiian Renaissance.

Despite many Japanese Americans attaining success in the islands, however, the community still dealt with the legal discrimination of the past. Throughout the 1980s, the paper covered the oral histories of aging Japanese Americans who were interred during the war, which helped to fuel reparation efforts by the U.S. government as well as the establishment of a national monument at Honouliuli, where Japanese were imprisoned from 1943 to 1946.

Through it all, the paper is careful to maintain journalistic objectivity. “Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals often don’t see eye to eye on issues,” Kanaizumi says. Whereas Japanese American readers might interpret a Japanese official’s vague remarks—or refusal to answer a question—as obfuscation, Japanese nationals are more likely to perceive them as an attempt to avoid incendiary comments or offense. Murata attributes this to the Japanese tendency toward aimai, or ambiguity. “We have to be neutral in our reporting,” he says, “and that takes time.”

A single day’s news takes approximately 60 hours to edit, and there’s as much to do in the translation of a paper as there is in the original reporting. The editors stress the importance of ba no kuuki wo yomu, or “reading the air,” a custom prevalent in Japanese culture that involves being attentive to the feelings and needs of those around you. “For our readers, this paper is a lifeline to their community, both here and in Japan,” Yoshida says. “There are many Japanese tourists who come to visit and want to know more about Hawai‘i by reading the paper. But most of our readers are living here, making Hawai‘i home while staying Japanese. That sense of pride—it’s the language that keeps people together.”