It’s show time at House Without A Key, but instead of taking the stage on Halekulani’s beachfront lawn like she’s done countless times over the past 46 years, Kanoe Miller is taking shelter from a typhoon. Tonight, the hotel’s resident hula dancer is on the opposite end of the Pacific from her typical post in Waikīkī, and her performance at House Without A Key at Halekulani’s sister property in Okinawa has been moved indoors due to the approaching storm.

In the more intimate setting of Halekulani Okinawa’s upstairs banquet room, the former Miss Hawai‘i has decided to improvise. “Let’s call people up out of the audience,” she says, turning to her band. “We’re going to have them dance.”

It felt like they were at home, Miller tells me the following day over Zoom, during a few hours of downtime in her hotel room overlooking the azure waters of Nago Bay. “That’s the way you would do it,” she says. “You talk to people, make them laugh, have fun. You share your hula with the audience as if they’re sitting in your living room.”

Despite her long tenure as a hula performer, Miller didn’t always consider herself an authority on the art form. In fact, when Kapi‘olani Community College approached her about teaching a series of hula seminars in 2009, more than 30 years into her career as a professional dancer, she initially declined. I’m no hula teacher, Miller thought. With so many worthy, credentialed kumu hula (hula teachers) on the island, she wondered, Why me?

As it turns out, the school was looking for an instructor unaffiliated with any of Hawai‘i’s established hālau hula (hula groups)—someone “neutral” who could serve as an ambassador of the dance for the seminar’s Japanese attendees. Reluctantly, Miller agreed to lead the class, on one condition: “I’m going to have to do it my way.”

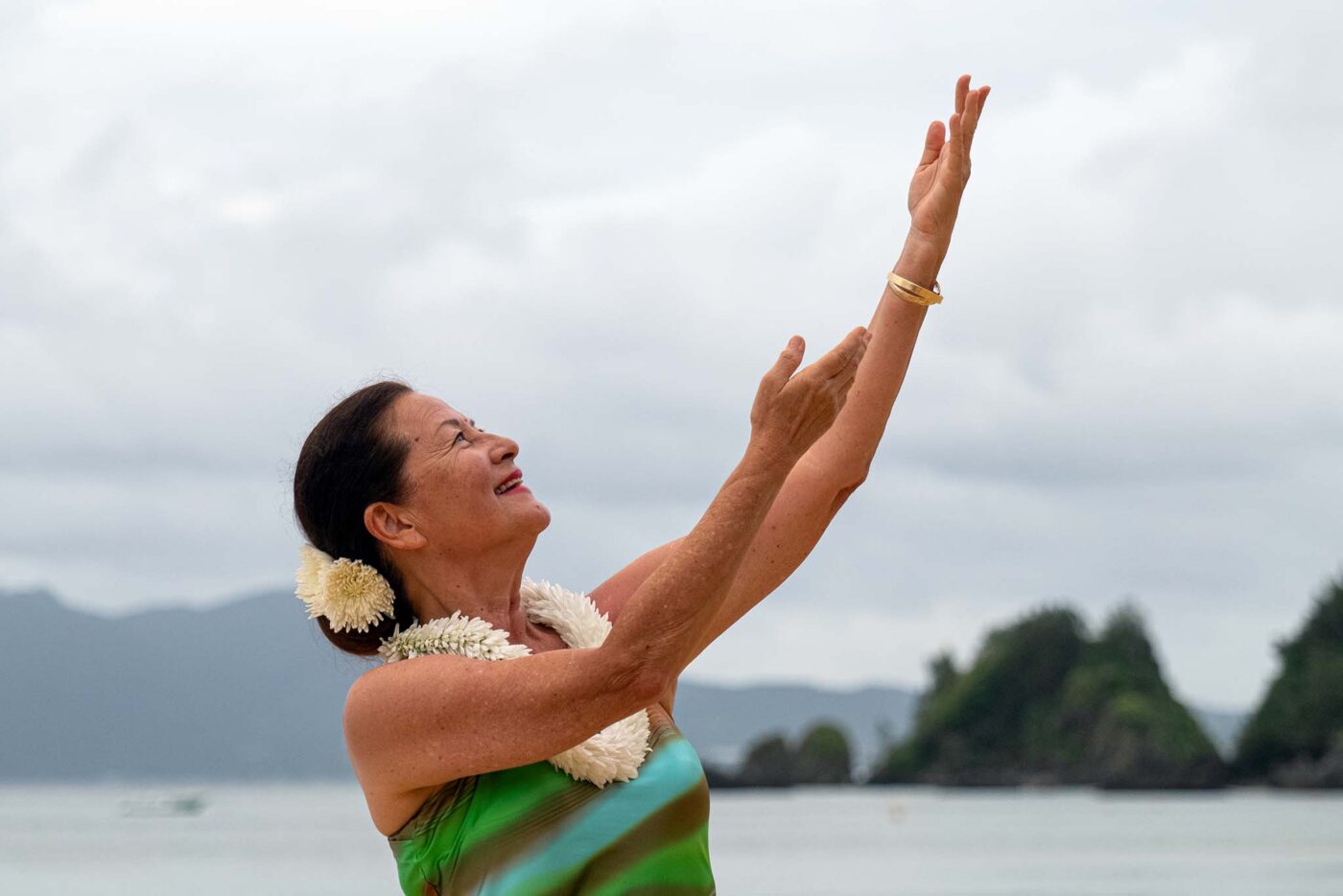

She spent the next couple of months developing a curriculum to teach not only the mechanics of hula, but the nuances that give the dance its significance and meaning: a gesture of the hand, a glint in the eye, a subtle tilt of the head. “Hula is storytelling,” Miller says. “You have to come to it with an open heart, that way, you can tell the story from your own experience.”

Over the ensuing decade, Miller made frequent trips to host workshops for her growing following in Japan, traveling back and forth to maintain her schedule of weekly hula shows at Halekulani. After the pandemic hit, putting an end to her usual pipeline of performing and teaching engagements, Miller and her husband, John, outfitted the living room of their Kāne‘ohe home with everything she’d need to bring her classes into the virtual realm: recording equipment, a sound system, studio lights, a 70-inch TV.

But when the time came for Miller to host her first Zoom class, she was met with a screen full of dancers moving to music heard at different times from their disparate corners of the globe. At the end of the session, Miller said goodbye to her students, shut off the screen, and wept, convinced that all the money and effort they’d invested in the endeavor had gone to waste.

In the absence of other revenue streams, however, the couple had no choice but to make it work. Miller took to dancing with her back to the camera so that students could follow along from behind, then learned to dance in reverse so she could turn around and mirror their movements. Most of all, she says, “I stopped expecting them to be synchronized and learned to see them as individual dancers.”

Focusing on one student at a time, Miller could offer pointers if she noticed a girl’s fingers were out of place, or if another wasn’t moving her hips correctly or flexing her knees enough. In calling out one student, she realized, others were quick to self-correct. She’d ask the class to turn off their screens while a select few performed, making clear that she was attuned to each and every dancer in attendance. From her days as a young entertainer, Miller was already in the habit of fixing her gaze on the camera when she spoke, and so she addressed her students the same way—as if she were looking them right in the eyes.

After nearly two years in lockdown, her life as a performer felt like a distant memory. The period of forced isolation enabled Miller to devote herself to her craft in a new way, granting her the time to dive into research, document new choreography, and build up an archive of recorded classes. “I went down to Waikīkī twice, just to drive through,” Miller says. “I didn’t miss it at all.”

That is, until Halekulani reopened and she felt the familiar thrill of being on stage. “When the music started and I heard the live harmonies, I wanted to cry,” Miller says. “It all came rushing in: This is who I am. This is where I belong.”

An entertainer at heart, Miller is back to performing every Saturday and every other Friday in Waikīkī, though she’s far from abandoning her second love of teaching. Hula classes continue to occupy the majority of her time—and they’re all still virtual, as she’s long embraced the opportunity to share hula with audiences both near and far. “Teaching hula, you have to study the words and teach your students to express them, so you’re sharing the stories of Hawai‘i in that way too,” Miller says before signing off, ending our Zoom call to get ready for the evening’s show.