Some 1,400 native plant species call this archipelago home, evolving across millennia to adapt to the islands’ distinct ecology. But the same conditions that created Hawai‘i’s unique ecosystems also leave them vulnerable. Today, Hawai‘i contains 44 percent of the country’s endangered and threatened flora. Because its native plants evolved in relative isolation, they have few natural defenses against outside threats. Invasive species, along with the impacts of climate change, habitat destruction, and human interference, have contributed to a rapid decline of native species throughout the archipelago, earning Hawai‘i the nickname “the extinction capital of the world.” More than 100 native plants have already gone extinct. About 27 are pronounced extinct in the wild, existing only in conservation centers and nurseries.

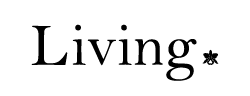

For some plants, their last chance at survival rests in seed banks, where they are stored in climate-controlled repositories with the hope that they can one day be replanted in the wild. Located in Mānoa valley, the Lyon Arboretum seed conservation laboratory is Hawai‘i’s largest and leading seed bank. It houses over 31 million seeds representing approximately 580 native plant species, more than 300 of which are considered threatened or endangered. It operates under the Harold L. Lyon Arboretum, a 200-acre botanical garden founded in 1918 and managed by the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

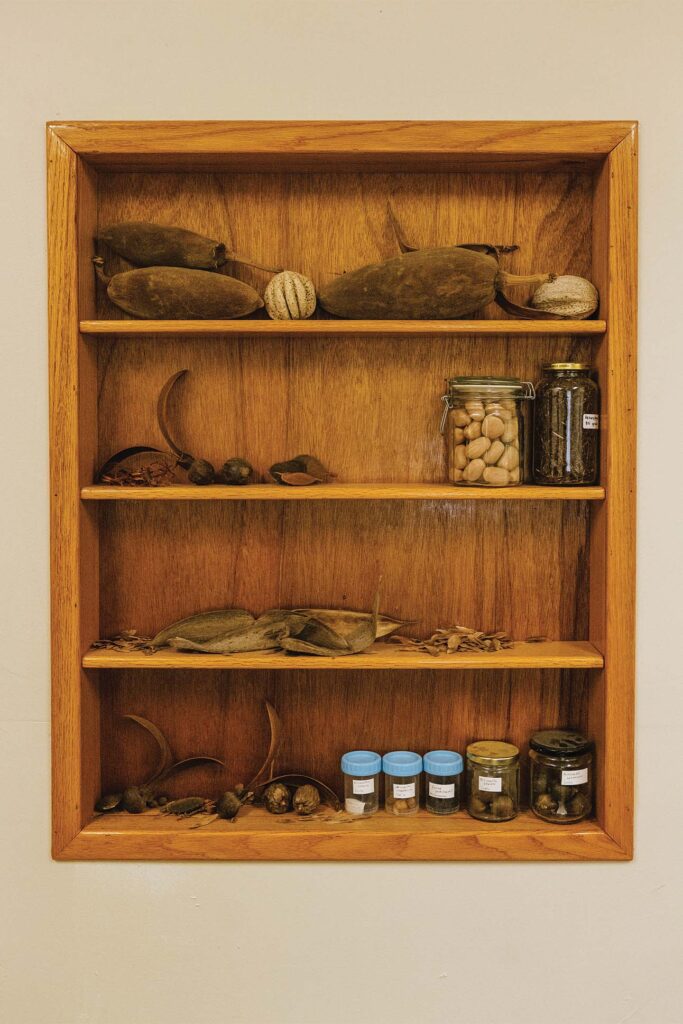

In 1992, the arboretum launched the Hawai‘i Rare Plant Program (HRPP), which established the seed conservation laboratory and its adjoining micropropagation lab and rare plant greenhouse. Under the guidance of UH Mānoa and in partnership with government and nonprofit agencies, the seed lab provides long-term storage and research to preserve the genetic diversity of the plants in its care, a necessary marker of resilience against invasive species encroaching on their habitats.

The seeds are collected by state organizations and other partners and sent to the lab, where they are germinated and observed for viability. The germination process is crucial, particularly for rarer species, as their lower inventory leaves little room for experimentation. Fortunately, the future is promising for the majority of native plants housed in the lab. Nearly 72 percent are “orthodox” seeds able to withstand the extreme levels of drying and freezing necessary for long-term storage, making them ideal for successful preservation. Some seeds, however, are too fragile for such conditions. “Intermediate” and “recalcitrant” seeds require more intricate refrigeration methods and can only be stored short-term or, in some cases, not at all. The seed lab is in the early stages of developing a cryopreservation method to house the seeds long term, but for now, they are sent to the micropropagation lab for temporary storage. Carefully cultivated seedlings are then sent out to rare plant nurseries, and from there, they are replanted at restoration sites throughout the state. Each year, thousands of plants are transported to the wild. Transitioning plants back to their natural habitats, though, presents its own challenges. Improperly prepared or inaccessible habitats, unnatural weather patterns, and inadequate manpower are all external factors that hinder seedlings from thriving once they leave the seed lab.

Still, conservation efforts proceed in earnest from mauka to makai (from the mountains to the ocean), where the seed lab is helping the small yet mighty seedlings reclaim their wilds.

Coastal Mesic Forests

Here, native plants mingle with sand, driftwood, and other coastal sediment swept inland by winds and salt spray. Skirting the slopes of the islands and stretching from sea level to over 1,000 feet, coastal mesic forests receive an even amount of rainfall and sunlight.

Naupaka kahakai (Scaevola taccada) is an indigenous shrub found along the coastline, notable for its hardy leaves and white half-blossoms. It provides a nesting habitat for seabirds and the Hawaiian yellow-faced bee, its main pollinator. One mo‘olelo (legend) tells of the star-crossed lovers Naupaka and Kaui: Jealous of their love, the fire goddess Pele banished one to the ocean and the other to the mountains, creating two varieties: naupaka kahakai (seaside) and naupaka mauka (inland). Another coastal species is pōhinahina (Vitex rotundifolia). The sprawling beach creeper has rounded, sage-like leaves and fragrant bell-shaped flowers that make it popular for lei making. It is also used in lā‘au lapa‘au, or traditional plant medicinal practices, to remedy ailments like skin irritations and back pain.

Mixed Mesic Forests

Hawai‘i’s mixed mesic forests are home to a wide diversity of plant life, ranging from ferns and shrubs to tall, canopying trees. Mixed mesic forests range from 1,000 feet to 5,000 feet in elevation and are neither wet nor dry, typically receiving a balanced amount of rainfall. Among the largest of these native trees is koa (Acacia koa), reaching up to 115 feet in height. Their long trunks and natural occurring oils make them a favored hardwood for carving. Only a fraction of the islands’ once-sprawling koa forests remain, as most were converted into sugar plantations and cattle ranches. Since their canopies provide a habitat for many native bird and insect species, their recovery is key to restoring native forests. Another species, ‘ōhi‘a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), is a common native plant whose specific name, polymorpha, means “many forms”— a reference to its wide-ranging colors and sizes, appearing as 2-foot shrubs or 50-foot trees. Traditional uses for ōhi‘a are still in practice today: its hardwood is used for carving, its flowers and leaves for lei-making, and its bark and fruit as medicine. Though ōhi‘a dominates Hawai‘i’s native forests, a fungus known as Rapid Ōhi‘a Death poses a threat to the population, killing some of the largest and oldest trees in a matter of days.

Wet Forests

Wet forests span the windward lowlands and montane heights of larger islands and, on smaller islands, thrive along the mountain tops. Lush with year-round vegetation, they generally grow at elevations ranging from 1,500 feet to 7,000 feet and beyond, with an annual rainfall of over 400 inches. Loulu, Hawai‘i’s only endemic palm tree, favors these moist conditions.

It earned the name loulu, Hawaiian for “umbrella,” for its large, fan-shaped fronds that provide shelter from the sun and rain. To this day, loulu is favored for thatching the roofs of hale, or traditional homes and structures, as well as for weaving hats and baskets. Increasing infestations of the coconut rhinoceros beetle has endangered loulu’s in-situ populations, a threat that the Hawai‘i Rare Plant Program is working urgently to address. Hāhā (Cyanea angustifolia), the native plants in the bellflower family, is another wet forest species. Known for its clusters of hanging petals, its foliage was traditionally wrapped in tī leaves and cooked in an imu (underground oven) or in times of food scarcity. Hāhā co-evolved with the long-billed native honeycreeper, one of its primary pollinators. Today many honeycreepers are extinct or endangered, posing a concern for the hāhā plant’s future. At the seed lab, hāhā and other culturally significant native plants find refuge—and hope for survival.