Kūkulu ka ‘ike i ka ‘ōpua.

Knowledge is set up in the clouds.

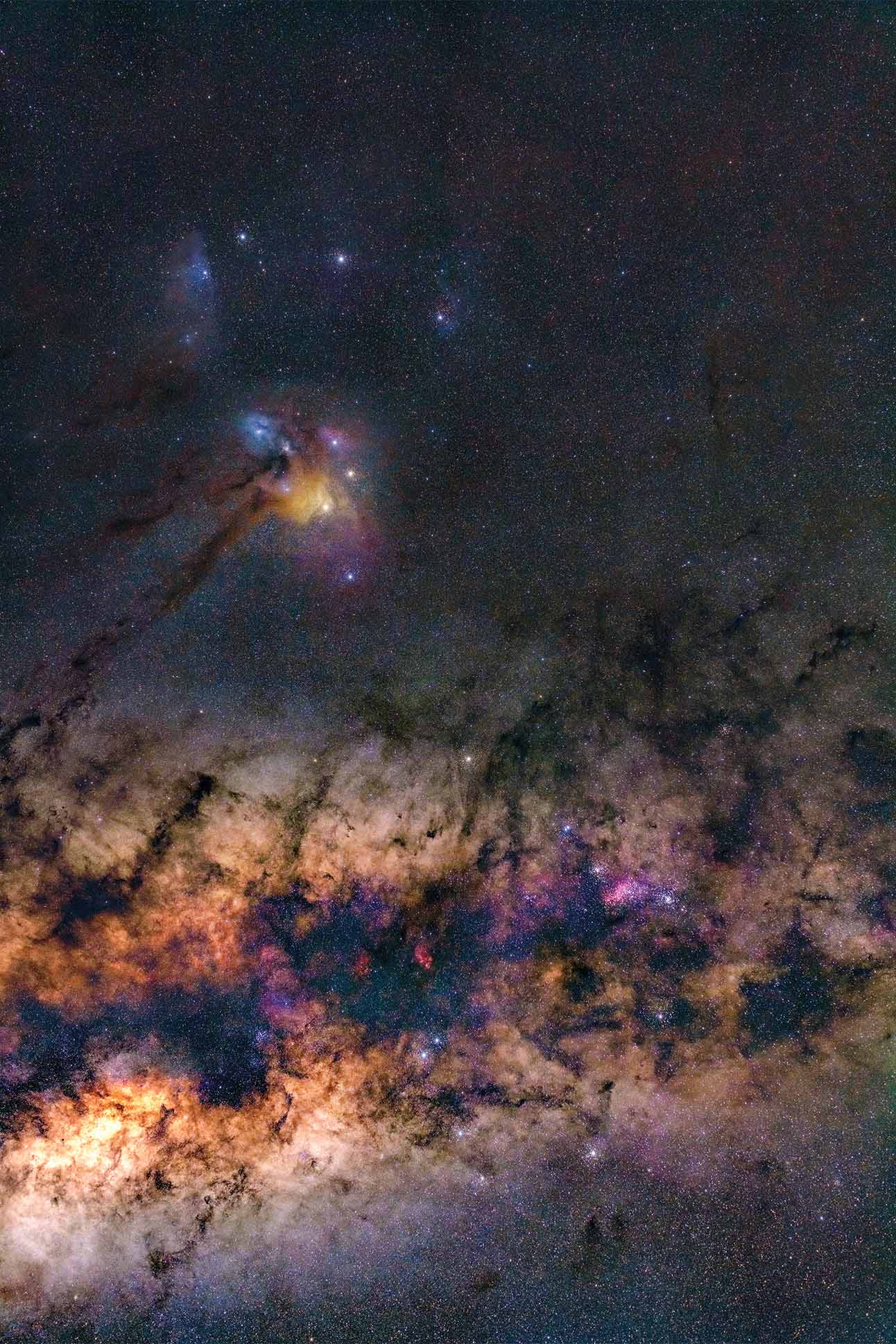

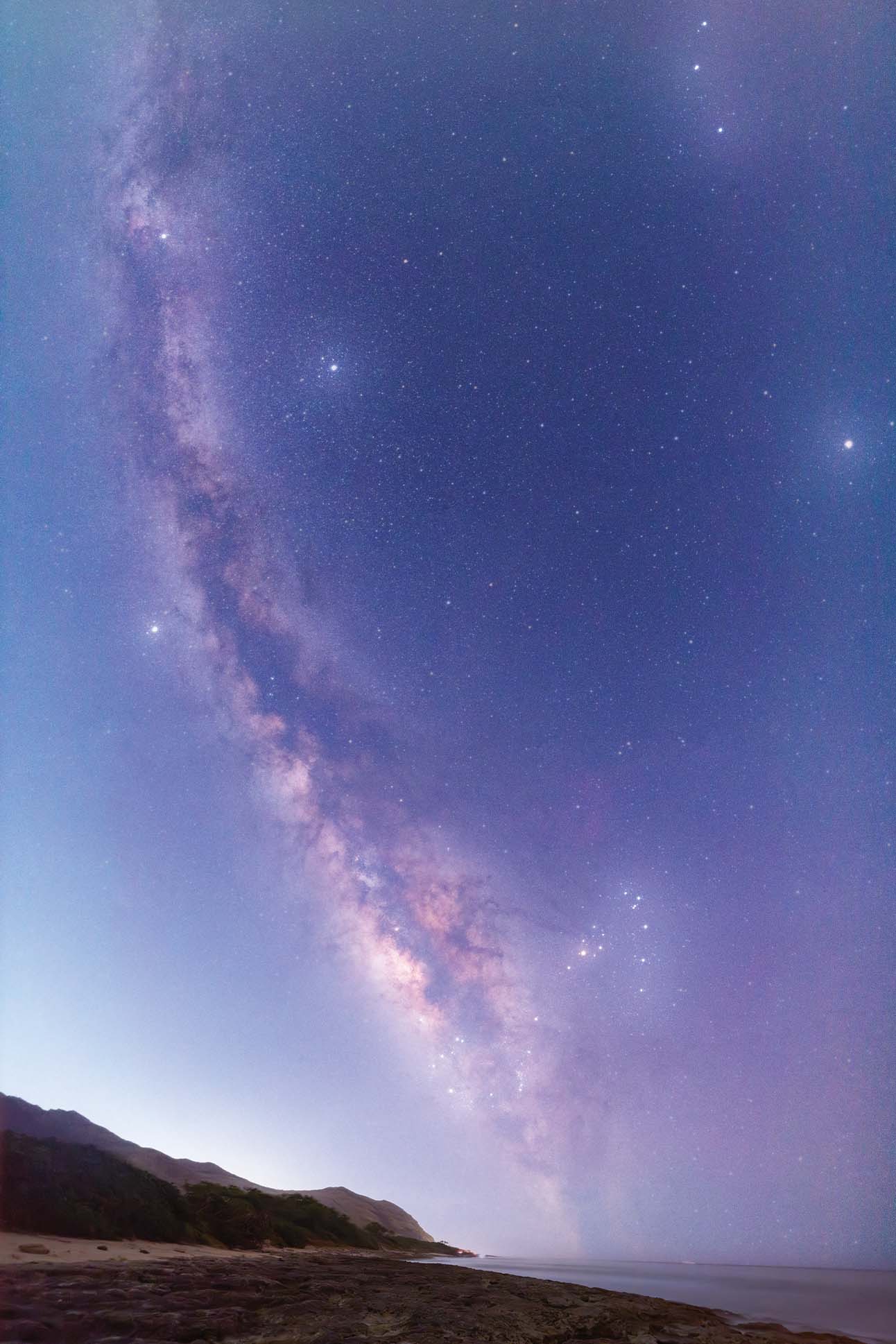

For visitors and kama‘āina alike, Hawai‘i’s skies are an endless source of beauty and wonder. We snap photos of dramatic sunsets and marvel at constellations shining overhead. Consider the name Halekulani, meaning “House Befitting Heaven”—the sky is an ever-changing canvas for the human imagination, inviting reflection, awe, and the sense that something greater lies in the view above.

For early Polynesians, the sky was more than a backdrop. It was a source of meaning and knowledge. Kilo, or skilled observers, studied it with intention, reading the clouds and tracing the movements of the stars for insight and survival.

Polynesians used the sky and other signals from the natural world to navigate thousands of miles of open ocean. They followed specific stars’ rising and setting points and observed the behavior of birds and clouds near land. This deep connection to the natural world allowed wayfinders to travel vast distances without modern instruments.

Much of this ancestral knowledge was lost in the wake of colonization and the suppression of Native Hawaiian culture that followed. However, the Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s helped revive traditional navigation techniques and other cultural practices that had nearly disappeared after Western contact. Today, modern wayfinders and kilo continue to recover and share this ‘ike (knowledge).

What follows are a few of the many constellations, clouds, and stars that Hawaiians look to for guidance. Each is a window into the way their kūpuna (ancestors) viewed and understood the world around them. The next time you pause to look up, let it be more than scenery—instead, see it as something speaking from beyond. Every star or passing cloud is part of a larger conversation between land, sea, sky, and spirit.

Makali‘i

In mid-autumn, a cluster of seven stars hangs low over the eastern horizon after dusk. Makali‘i, known to the Western world as Pleiades, symbolized a change in season and social activities in early Hawai‘i. Its rising announces the Hawaiian new year and the beginning of Makahiki season, a time of peace, harvest, and spiritual renewal dedicated to the god Lono. This seasonal transition is one of the most important in the Hawaiian calendar. According to mo‘olelo (legend), Makali‘i was named for a selfish chief who collected food as tax in times of scarcity. Instead of helping his people through famine, he hung a net of food in the sky, where they could not reach it. A mouse named ‘Iole climbed into the heavens and gnawed through the net until the food tumbled back to Earth, saving the people from starvation. Today, Makali‘i remains a harbinger of ho‘oilo (the wet season), signaling that cooler temperatures and winter rains are near.

Ao ‘Īlio

He hō‘ailona ke ao i ‘ike ‘ia.

Clouds are recognized signs.

Ao ‘īlio, or “dog clouds,” roll in packs across the sky. Often appearing dark, long, or patchy, these stratocumulus clouds were thought by early Hawaiians to embody the aggressive spirit of Kū, the god of war. Ao ‘īlio signal a change in weather, often bringing rain or wind within hours. Kilo believed these clouds carried omens and used them to predict future events.

Manaiakalani

In summer and fall, the hooked curve of Manaiakalani dominates the southern sky. In mo‘olelo, Manaiakalani is the demigod Māui’s sacred fishhook, which he used to pull the islands of Hawai‘i up from the ocean floor. Closely related to Scorpius, this familiar constellation is part of Nā ‘Ohana Hōkū ‘Ehā, or the Four Star Families. Developed by contemporary Hawaiian wayfinders, this system groups the night sky into four seasonal star families, organized by season and direction. Navigators use Nā ‘Ohana Hōkū ‘Ehā to memorize where important stars rise and set on the horizon. Manaiakalani is a celestial compass point, helping voyagers stay on course across long ocean distances.

Hōkūle‘a

Known as Arcturus in Western astronomy, Hōkūle‘a is a zenith star in Hawai‘i, passing directly over the islands. Like Manaiakalani, Hōkūle‘a is part of Nā ‘Ohana Hōkū ‘Ehā and plays a central role in the star compass, helping navigators find both direction and latitude. For Hawaiian wayfinders, seeing Hōkūle‘a overhead tells them, “You’re home.”

In 1975, the Polynesian Voyaging Society named its double-hulled canoe Hōkūle‘a in honor of this guiding star. The canoe’s maiden voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti, using only traditional navigation methods, proved that early Polynesians were capable of long-distance ocean exploration, something Western scholars had long denied. Hōkūle‘a’s name, meaning “Star of Gladness,” reflects its significance in Polynesian voyaging: After a long journey, seeing it overhead indicates safety and success.

Ao Manu

Delicate tufts known as cirrus clouds appear at high altitudes, like brushstrokes across the sky. Early Hawaiians named them ao manu, or “bird clouds.” These feather-like formations are made entirely of ice crystals. Ancient kilo predicted high winds when groups of ao manu appeared. Modern weather forecasters agree—many cirrus clouds signal an approaching front or shift in weather.

Ao Hekili

When ao hekili, or thunderclouds, darken the sky, it means Kāne-Hekili is near. Kāne-Hekili is the Hawaiian god of thunder, a sibling of Pele and a powerful force in the natural and spiritual worlds. Families who claim thunder as an ‘aumākua (family god or ancestor) worship him. During storms, Kāne-Hekili’s devotees remain silent to honor his kapu (law). It is said that when he visits his followers in dreams, he appears in human form, black on one side of his body and white on the other.

Chiefs and kahuna (priests) who claimed Kāne-Hekili as an ‘aumākua were often commanding leaders. One kahuna from East Maui was said to be possessed by the god’s spirit and could summon thunderstorms to protect himself. Maui’s last ruling chief, Kahekili, was tattooed entirely on one side to show he was kin to the thunder god. Today, ao hekili is a powerful reminder of nature’s force and might.