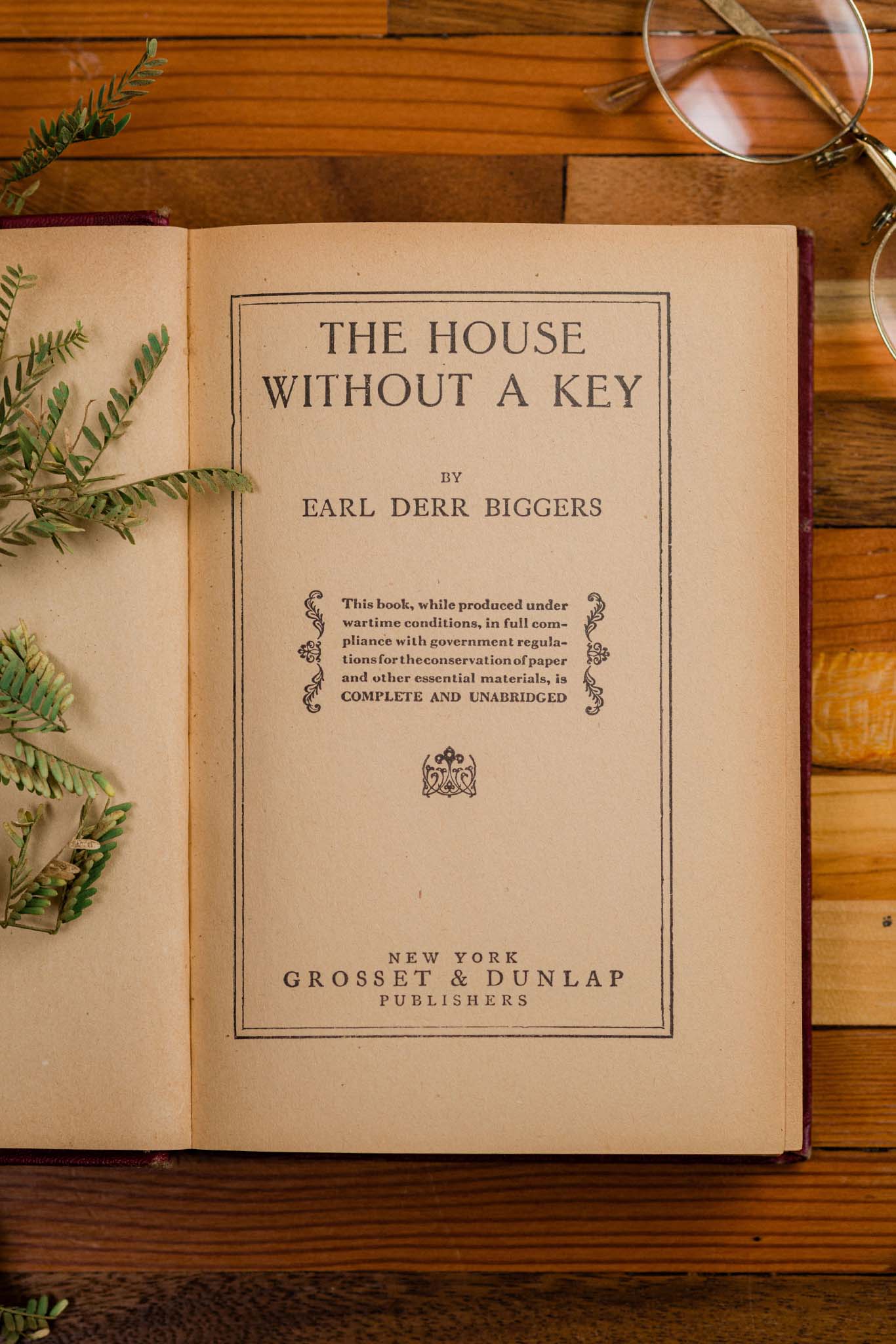

“That’s how the murder happens,” says Hi‘inani Blakesley, cultural advisor at Halekulani, as we stand in front of the hotel, facing Kawehewehe channel. It is the same channel that Kamehameha the Great sailed through in 1795 to land his troops on O‘ahu in his mission to unite the islands, Blakesley tells me. It is a clear, wide channel of sand through Waikīkī’s reef, stretching all the way to the breakpoint, where today we can see surfers waiting for waves at Pops. This is the channel that (spoiler alert) enables the murder in Earl Derr Biggers’ The House Without a Key.

In 1919, Biggers stayed at the hotel Gray’s-By-The-Sea, which stood near where we are now, and where the idea of the novel came to him. Many people know that Halekulani’s bar and restaurant House Without A Key was named after the novel, but few realize the story’s title itself was inspired by the hotel he stayed in, previously J.A. Gilman’s home, an actual house without a key—and so the name comes full circle.

Despite loving Raymond Chandler’s detective novels of the same era, I had never read The House Without a Key until now. Part of it might have been the idea of a Chinese detective written by a white person in the ’20s—I pictured something like the ridiculous bucktoothed Mickey Rooney playing Mr. Yunioshi in the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s. But when I picked it up recently, I was captivated. Sure, there are cringe-inducing moments, particularly in detective Charlie Chan’s stilted speech, but Chan is also often depicted as the most observant and smartest person in the room—particularly astonishing in the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act. It turns out, Biggers was inspired by a real-life Chinese police detective in Honolulu at the time, Chang Apana, who stood at 5 foot 3 and carried only a bullwhip. The stories about him are legendary: the time he rounded up 40 gamblers single-handedly, the time he was thrown from a second-story window and landed on his feet, the time he had been run over by a horse and buggy.

see what Biggers saw almost a century ago in Honolulu, to realize what is gone, and to recognize what remains.

Charlie Chan launched Biggers’ fame, spawning six books and more than four dozen movies centered on the detective, but it’s the quieter moments of the book that really draw me in, the snapshot of Hawai‘i in the 1920s. Among many depictions of the era, Biggers describes a trolley that “swept over the low swampy land between Waikiki and Honolulu, past rice fields where bent figures toiled patiently in water to their knees, past taro patches, and finally turned on to King Street … [past] a Japanese theater flaunting weird posters not far from a Ford service station, then a building he recognized as the palace of the monarchy.” To read the book is to see what Biggers saw almost a century ago in Honolulu, to realize what is gone, and recognize what remains. There’s the kiawe tree under which a character smokes every night, the tree which fell in 2016, but still stands—and grows—in front of House Without A Key with the same resiliency that has enabled it to live since 1887. There is also, by the small, sandy beach fronting the hotel, Halekulani’s oldest hau tree, which even a hundred years ago was “seemingly as old as time itself,” wrote Biggers in The House Without a Key.

But what is really as old as time itself: nostalgia. Even in the 1920s in Hawai‘i, Biggers’ characters long for what once was. “‘The ‘eighties,’ [Winterslip] sighed. “Hawaii was Hawaii then. Unspoiled a land of opera bouffe, with old Kalakaua sitting on his golden throne.’ … ‘It’s been ruined,’ he complained sadly. ‘Too much aping of the mainland. Too much of your damned mechanical civilization—automobiles, phonographs, radios—bah! And yet—and yet, Minerva—away down underneath there are deep dark waters flowing still.’”

‘

Not long after Biggers’ visit to Hawai‘i, Halekulani acquired Sheriff Arthur Brown’s home, the present-day site of House Without A Key. The hotel where Biggers stayed, Grays-By-The-Sea, closed, and Halekulani bought that too. Waikīkī was already rapidly changing in the ’20s, and as I idle at House Without A Key at sunset—the time that Biggers likely loved best in Waikīkī, based on his descriptions—I see more people, more buildings, more “mechanical civilization” than Biggers did during his stay. And yet, just as the deep, dark waters still flow in the springs under Halekulani, it is hard not to be swept into the age-old spell of Waikīkī while facing the ocean and listening to the De Lima ‘Ohana sing Queen Lili‘uokalani’s “Aloha ‘Oe”—“the most melancholy song of good-by,” Biggers declares in The House Without a Key—and to know that someday, despite grumbling about how much life has changed, we will remember these days by the kiawe tree, right now, with fondness.