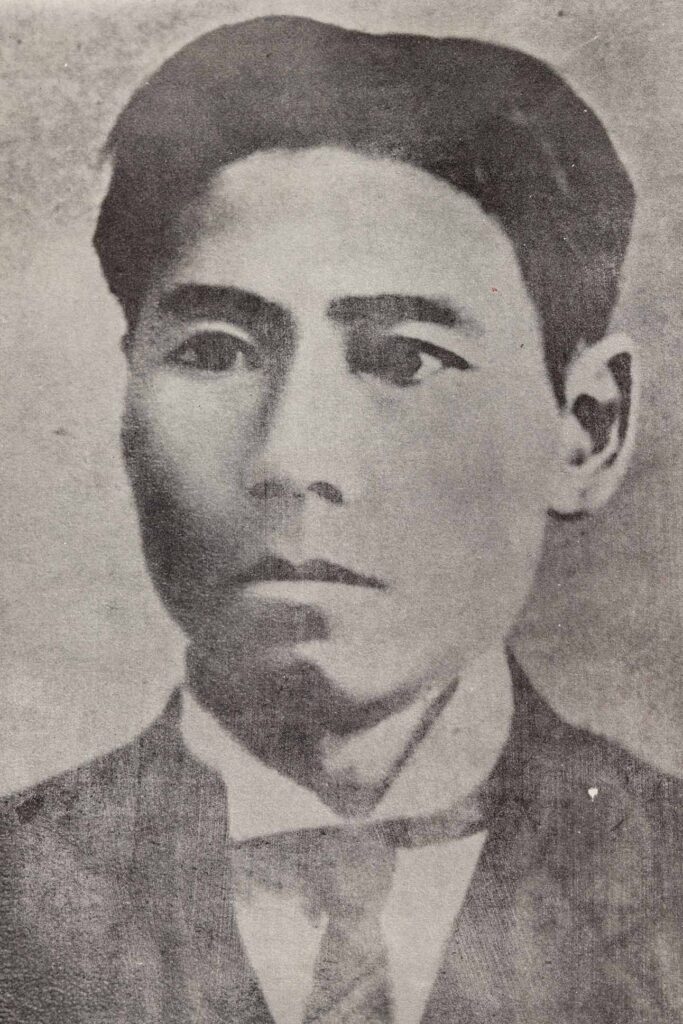

We all have a story about where we came from, one that is the byproduct of a swirling combination of geopolitical, economic, and other forces that have collectively shaped us and wherever we call home. The more than 50,000 people of Okinawan descent living in the state of Hawai‘i today can trace this trail through the narrow gate of one man: Kyuzo Toyama, a young Okinawan who lived and worked over 120 years ago.

Born in 1868 in the town of Kin on Okinawa’s eastern coast, Toyama arrived in a world on the precipice of change. Until 1879, the Ryūkyū Kingdom ruled the chain of sandy, volcanic islands located between southern Japan and Taiwan. Following the Meiji Restoration in mainland Japan, the Japanese government sought to quickly modernize and expand—annexing Okinawa as a prefecture shortly thereafter. A young Toyama, 11 years old at the time, would go on to witness his island home change dramatically.

“Understanding Toyama’s place in history is also understanding the history of discrimination and colonization from Japan,” explains Norman Kaneshiro, co-director of Ukwanshin Kabudan, an O‘ahu-based group dedicated to Okinawan classical arts. This colonial relationship could be felt throughout Okinawan society: in the installment of government officials from other Japanese prefectures in high-ranking Okinawan positions, in the banning of the Okinawan language in schools, in the sentiment toward Okinawan traditions like raising pigs and practicing hajichi, the tattooing of a woman’s hands, which were looked down upon by mainland Japanese.

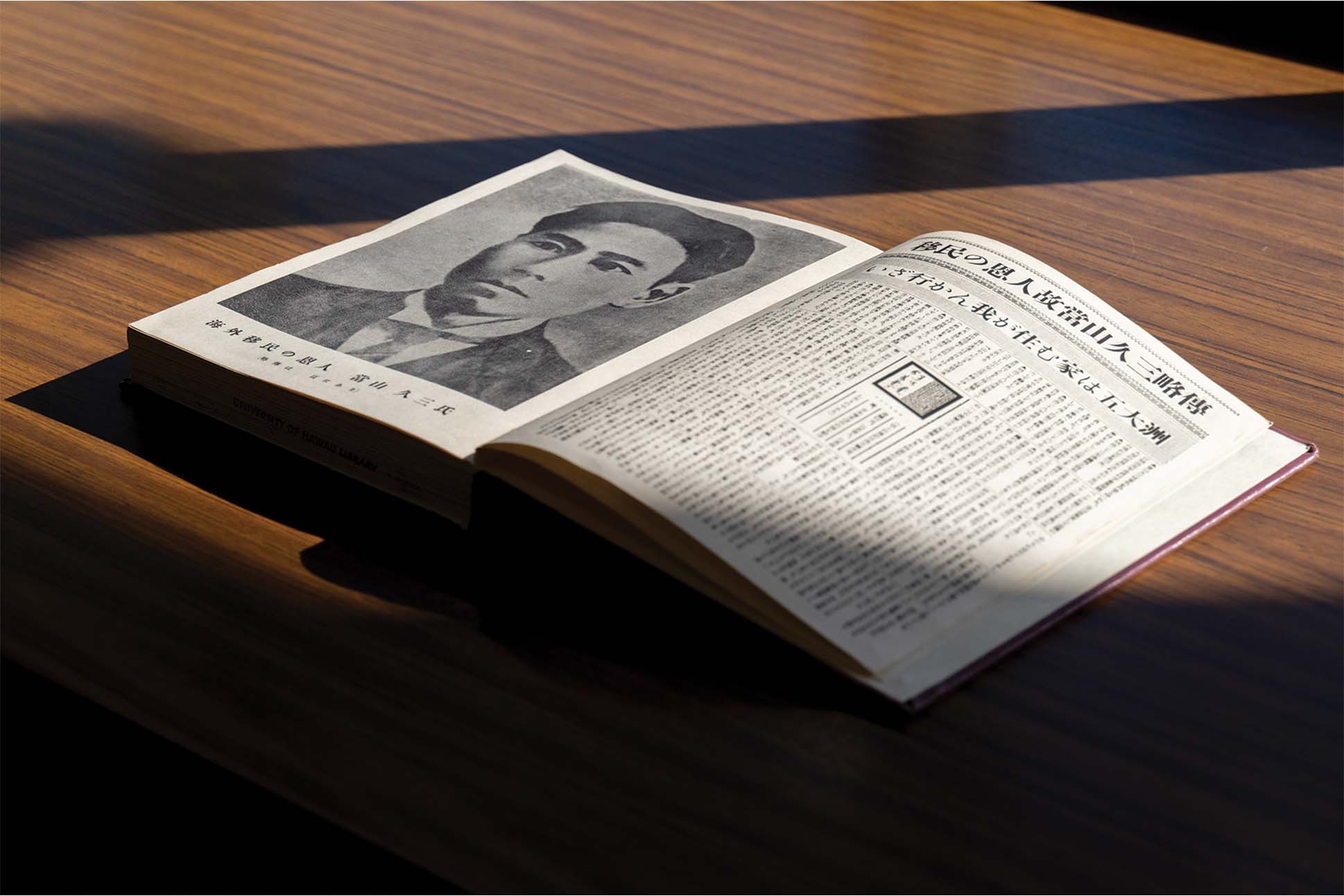

It was while studying in Tokyo for two years that Toyama formulated a theory of economic improvement for his home island. Influenced by his friendship with Okinawan civic leader Noboru Jahana, along with his own independent studies, Toyama theorized that Okinawan migrant laborers could fortify the Okinawan economy by working abroad and sending money home—spurring growth for the struggling island beleaguered by an expanding population and scant resources.

Upon returning home from Tokyo, Toyama set about convincing others, most notably the governor of Okinawa, Shigeru Narahara, of the merit of his plan and the right of Okinawans to follow the example of mainland Japanese and emigrate. “Toyama asked, ‘If the mainlanders can emigrate, why can’t we, the Okinawans, emigrate?’” explains Masato Ishida, director of the Center for Okinawan Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “Okinawans deserve the same kind of freedoms.”

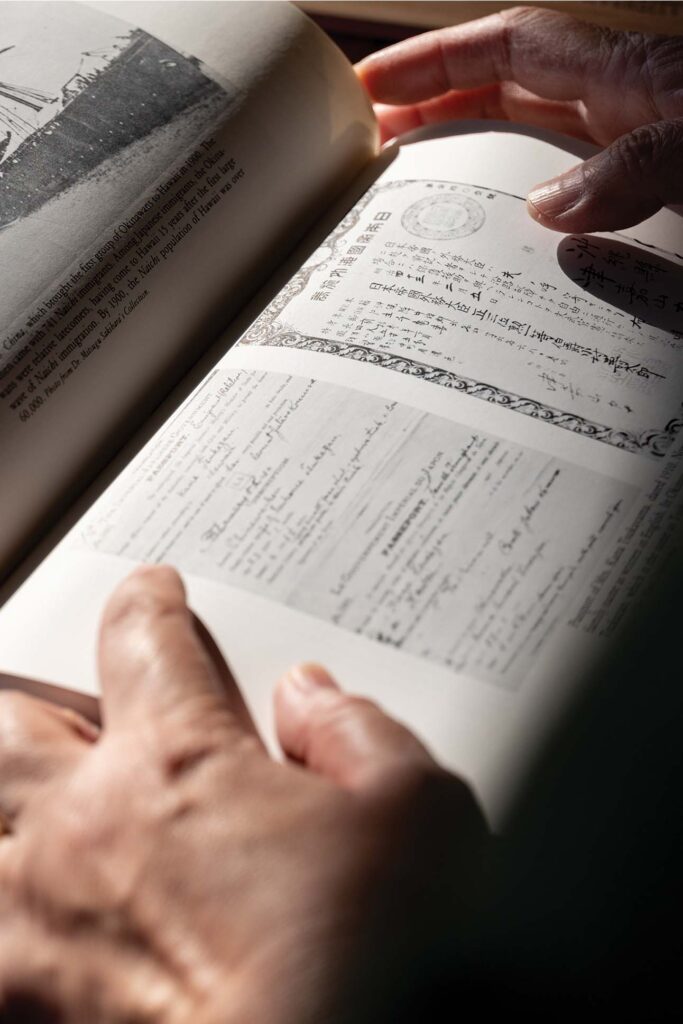

Eventually, the governor reluctantly agreed, and Toyama gathered an intrepid group of young men, ages 21 to 30, to relocate to Hawai‘i.

While daring in his ambition and verve, Toyama seemingly did not account for the harsh reality that awaited these migrants. Arriving on O‘ahu on January 8, 1900, the 26 immigrants quickly found themselves confronting a climate of hardship and oppression. Bound to labor contracts on sugar plantations, they toiled under a heavy sun and hot whip, enduring brutal working conditions worsened by the discrimination they faced from the mainland Japanese workers on the plantations. “Emigration didn’t happen in a vacuum,” Kaneshiro says. “Okinawans were immigrant laborers within Hawai‘i’s own colonization by the United States.”

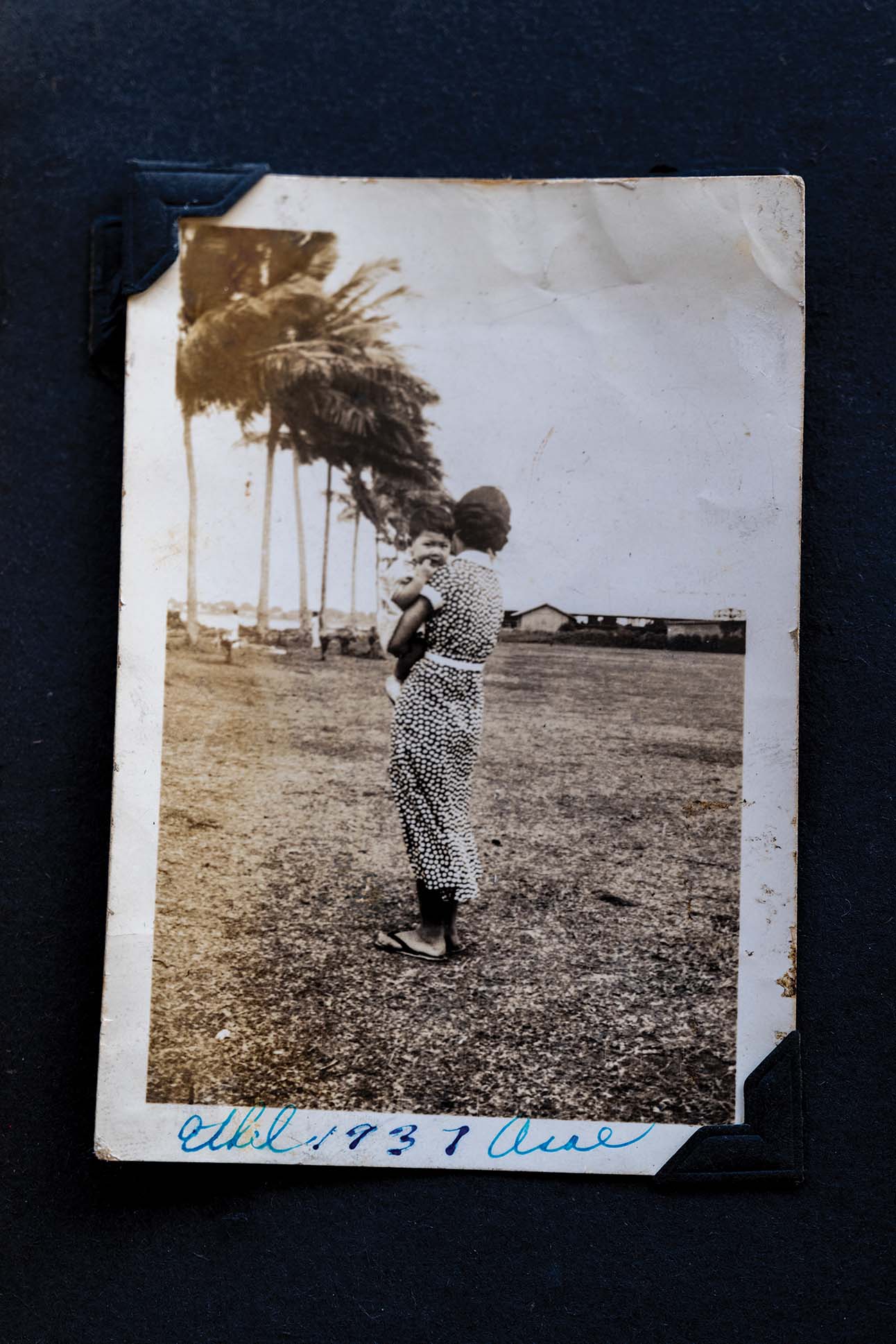

According to Lynette Teruya, the Okinawan Studies librarian at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, the way Okinawans talked and dressed set them apart from the naichā (mainland Japanese) communities that immigrated to Hawai‘i before them, starting in 1868. “The Okinawans were the newcomers in an already-established Japanese community,” Teruya says. “Some of them were made to feel embarrassed about their practices.”

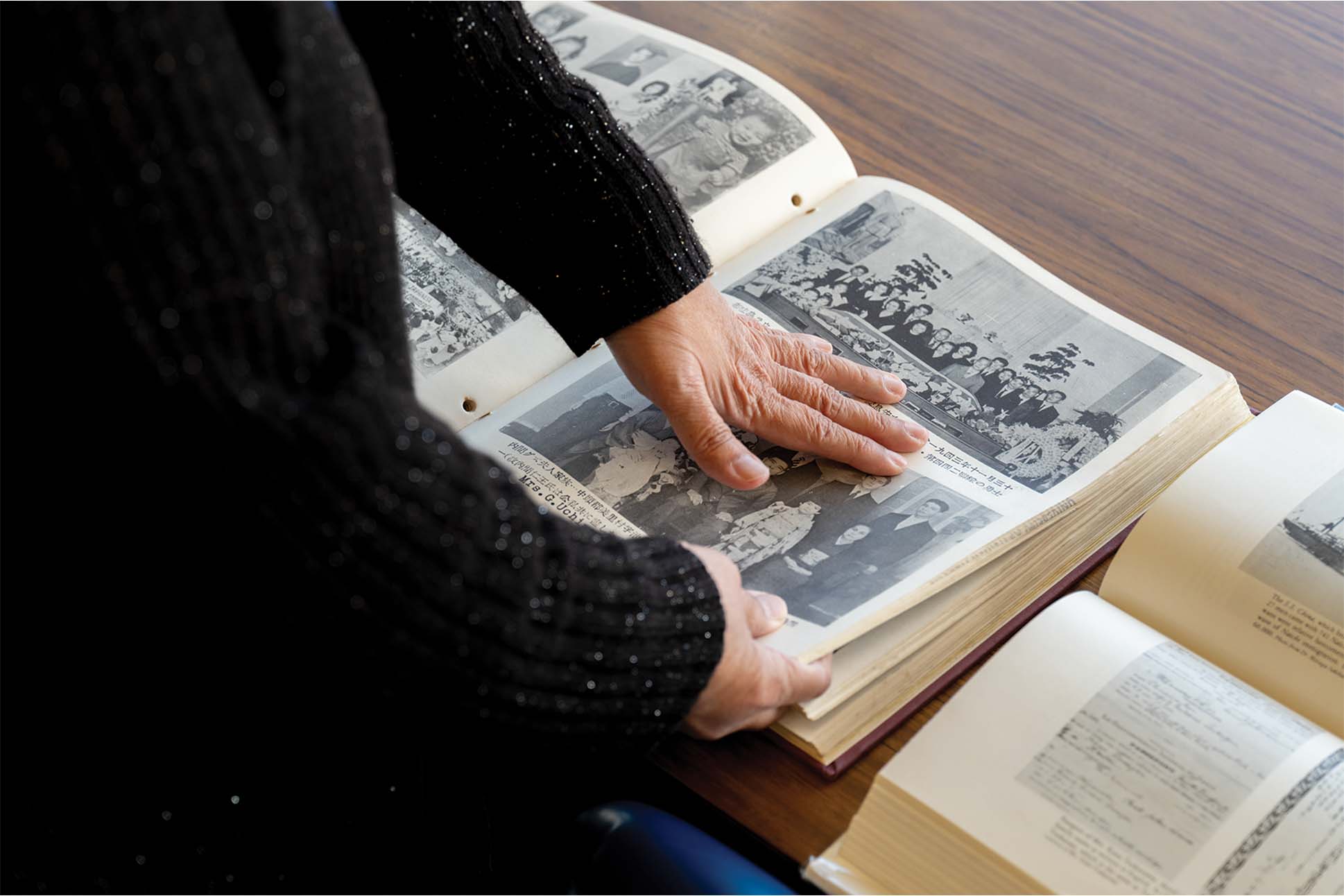

Nevertheless, Okinawans continued to immigrate to Hawai‘i, including Toyama, who arrived in 1903. By 1924, over 16,000 Okinawans had made the journey. Today, their descendants continue to explore the complexities of Okinawan identity while navigating life far from their ancestral homeland. “I grew up hearing how important it was to be Okinawan but not knowing exactly what that meant,” says Kaneshiro, who was born in Hawai‘i but whose grandparents are all from Okinawa.

Since World War II, when the Nisei (second generation) of naichā and Okinawans banded together to form the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team—the most decorated military unit in American history—divisional tensions between Hawai‘i-born Okinawans and Hawai‘i-born Japanese have diminished. “There’s been a change in attitude about what it means to be Okinawan,” Teruya says. “People really started to feel proud.” That pride has blossomed into annual Okinawan fairs, leadership summits, and dedicated cultural groups throughout the state, many of which celebrate Toyama’s legacy.

While Okinawan heritage is a source of pride for many of Okinawan descent in Hawai‘i today, Toyama remains a more complex subject—his legacy intertwined with the histories of two colonized island nations, both shaped by migrant labor. “Toyama was not afraid of challenging political authorities,” Ishida says, emphasizing the significance of his writings, advocacy, and leadership in guiding immigrants to Hawai‘i. “In that sense, he is a symbol of freedom for Okinawans.”

Still, Kaneshiro cautions, “It’s very easy for us to romanticize the work that Toyama did. It’s important to really closely examine the motivations and the climate around how these events happened.” Yet for the tens of thousands of Okinawan descendants born in Hawai‘i, Toyama’s impact is undeniable. “I’m grateful that he made that effort,” Teruya says. “Without him, the Okinawans probably wouldn’t have been here.”

For Toyama, the man who started it all, life ended in 1910, shortly after securing a seat in the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly. His ashes were interred at Mililani Memorial Park on O‘ahu. Today, he is honored with statues in his hometown of Kin and on O‘ahu. In Kin, Toyama’s statue faces Hawai‘i, his stone eyes challenging the vast distance between.