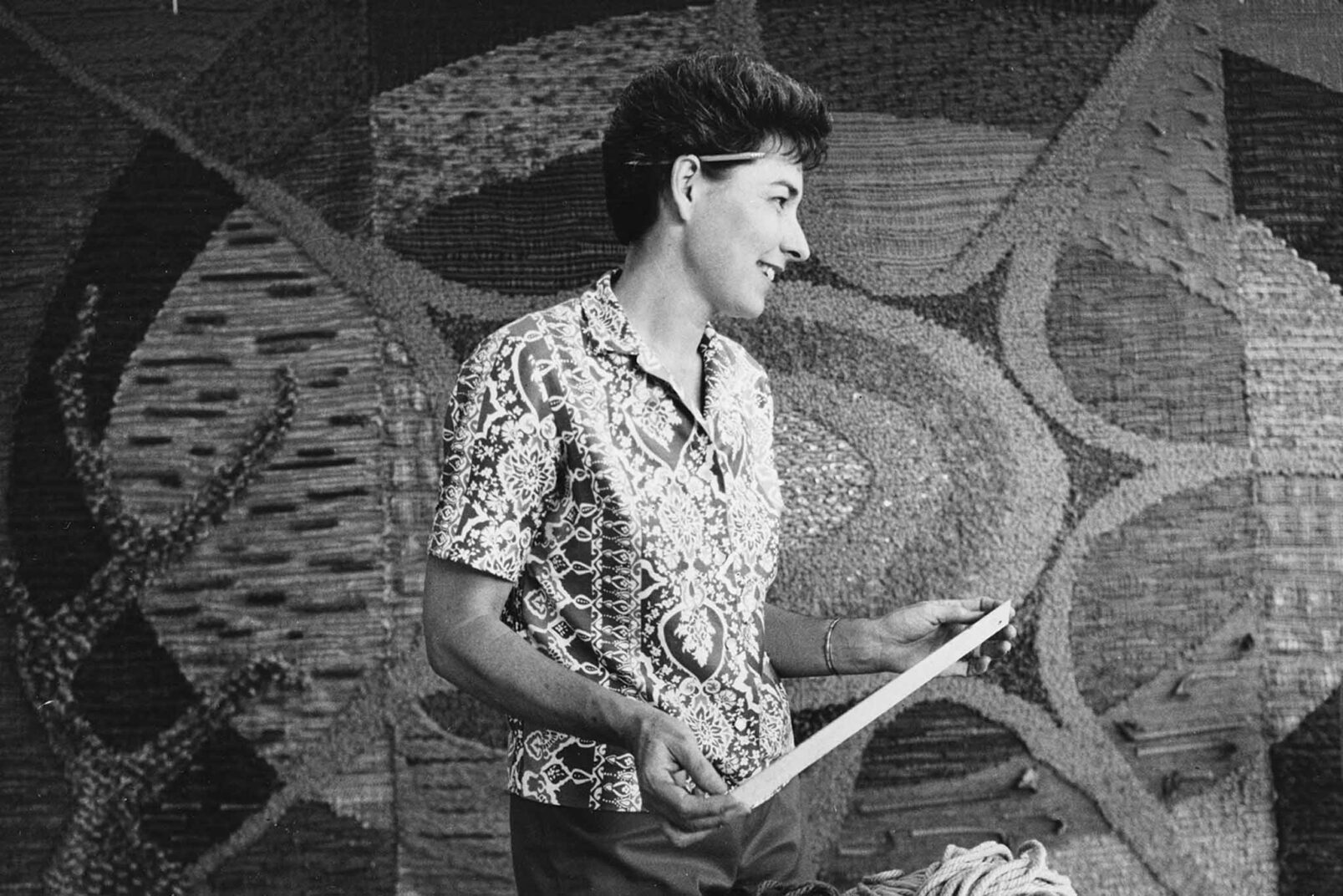

For Ruthadell Anderson, there was something special about working with fibers, about creating on a loom. Perhaps it was the detailed planning, the delayed gratification. Maybe it was the tactile play of texture and color, or the ritual labor of weaving weft through warp. She had practiced ceramics and tried her hand at metalwork, but weaving was the art form that kept her interest for decades, during which she pushed the limits of ancient tapestries and modern murals with an aesthetic both abstract and reflective of Hawai‘i’s environment.

One of Anderson’s compelling traits was her ability to make work sized to the architectural spaces within which they would live. Her 1966 breakout creation, a 15-by-8-and-a-half-foot tapestry inspired by the Hawaiian legend of Maui ensnaring the sun, exemplified this place-based sensibility. It was created for the Bank of Hawai‘i Waikīkī building, now the Waikīkī Galleria Tower. The piece was a textural geometric interpretation of a sun, with colors and fibers inspired by Hawai‘i and featuring local materials like banyan roots and hau fibers. Made in five pieces, it took 400 hours and two assistants to complete.

The Bank of Hawai‘i tapestry was not Anderson’s first time working with local materials, or with other weavers. By 1966, she had spent 20 years exploring the craft and growing her circle of local makers and artists. Born and raised in San Jose, California, she moved to Hawai‘i in 1947 at 25 years old with her first husband, Claude Horan. He had been invited to start the ceramics program for the University of Hawai‘i by Hester Robinson, a professor who began teaching its first fiber arts classes a year earlier. At the time, Anderson’s focus was on ceramics, but her background in weaving naturally drew her to Robinson.

By 1951, Anderson and Robinson were working together to demonstrate weaving’s commercial potential on behalf of the Industrial Research Advisory Council, a government committee exploring promising industries for the Territory of Hawai‘i. They wove local materials like palm midribs and haole koa into table mats and lamp shades for public display. Throughout the decade, Anderson immersed herself in the Hawai‘i crafts scene, among other things working as a weaver for a local studio and developing the Hawaiian Craft Association. She was one of the founding members of Hui Mea Hana, which was spearheaded by Robinson and was the precursor to Hawai‘i Handweavers’ Hui, one of the largest fiber arts groups in the state today.

In 1963, Anderson returned to UH for her MFA in weaving with the goal of opening her own studio. She saw a growing demand for original weavings “both for residential use and for public buildings,” she said in her entry for Francis Haar’s compendium Artists of Hawai‘i: Volume II. Post-World War II, the growing real estate market and tourist economy created a demand for custom textiles.

She graduated in 1964 and opened a studio and shop in a little house in Waikīkī with ceramist Louise C. Guntzer. Swiftly, Anderson garnered commissions that balanced art and function, including wall hangings for Sheraton Kauai, Royal Aloha Hotel, and Kauai Surf Hotel and blinds for Woolworth’s Ala Moana and the Hawaiian Airlines Waikīkī office.

By the time the State of Hawai‘i Fine Arts Committee announced they were commissioning artworks for the new State Capitol building in 1967, including wall hangings behind the rostrums of both legislative chambers, Anderson had established her reputation in the art form. Anderson was selected for the House wall hanging. It would be the largest project she would ever undertake.

The work took several years to plan, make, and install and required more than a dozen weavers to produce. After seeing her House wall hanging, the Senate chose Anderson for their installation as well. The final creations, each 39 feet high, hug the concave walls of the Senate and House chambers. Abstract in nature, each features an interplay of geometric shapes in hues of Hawai‘i—one of the earth in deep reds, oranges, and browns; the other of sky, water, and sand, blue hues surrounded by tans.

Anderson went on to make murals as far flung as Tahiti. She created a series of 11 fiber sculptures for the Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole Federal Building that hung from the ceiling of the first-floor lobby. She wove a series of large wall hangings for architect Vladimir Ossipoff’s 1970 remodel of the International Terminal Building at the Honolulu International Airport, leaning into a simplistic aesthetic of bright colors, lines, and geometric shapes. Her 6-by-13-foot wall hanging for Kaua‘i Community College titled “Wailele,” meaning “leaping water,” is a lush geometric abstraction of a waterfall: blues and purples flowing through blocks of browns and greens reminiscent of both lo‘i and Midwest agriculture. Over her career, her aesthetic morphed to match the demands of her clients and her own experimentation in fiber and form. Throughout, she played with abstract shapes, lush colors and texture, Polynesian inspiration, and the sculptural qualities of the craft.

Anderson’s large-scale installations often required more than one weaver to produce. Her success in pulling off such projects locally speaks volumes about her connections in the Hawai‘i artistic community. In fact, while weaving seems like a solitary act, Anderson nearly always made her commissions with an apprentice or collaborator. “I really enjoy the stimulation of working with others,” she said in Artists of Hawai‘i: Volume II. “The creative act gives me the most satisfaction.”

In her lifetime, Anderson mentored dozens of weavers. “She was so important to the fiber scene here,” said Barbara Okamoto, who met Anderson through Robinson when studying weaving at UH and later worked at Anderson’s Loom Originals store in Kaimukī. Back when weaving was still largely deemed a craft rather than an art form, Okamoto recalls that there was never any doubt that Anderson was an artist.

Upon moving to Hawai‘i in 1947, Anderson immersed herself in the local crafts scene and sourced inspiration and materials from the world around her.

But, according to Okamoto, recognition as an artist wasn’t something Anderson prized. Rather, she remembers Anderson encouraging fellow weavers and fretting over the pricing of materials, wanting them to be accessible to the community. Cathy Levinson, who frequented Anderson’s store to shop and talk story, recalls that “Ruthadell created a warm atmosphere of artistic creation and support for weavers.”

One of Anderson’s later works, which is now among the collection of the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts, is a rectangular weaving of black yarn about three feet long, with white fibers projecting along its center. Titled “803 Whiskers” and made with whiskers shed by her cats, the piece is stark and masterful yet also tender and humorous. It leaves an impression similar to that of Anderson herself, who came across as serious and direct at first but was generous and funny, according to those who knew her.

For decades, Anderson dedicated her life to the work of weaving—an act of care and intention, of improvisation and reflection. Even now, after her passing in 2018, Anderson’s archives are in the company of the Hawai‘i Handweavers’ Hui on the second floor of a building in Chinatown, where looms clatter and click and weavers honor what came before, working together to shape what comes next.