Long before his art would adorn the walls of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Guggenheim, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Maui-born Tadashi Sato was one of a growing number of nisei, or second-generation Japanese Americans, coming of age in Hawai‘i in the 1930s. The cultural traditions upheld by Sato’s family, along with his daily routine of diving and fishing, and his fascination with the rural landscape of his home in Kaupakalua, East Maui, laid the groundwork for a lifelong pursuit of creative expression through pen and ink, oil, and mosaic. His father was a calligrapher; his grandfather practiced sumi-e, a monochromatic ink painting style rooted in Zen Buddhist themes of nature and intuition. Throughout Sato’s foray into Abstract Expressionism, such cultural undercurrents of minimalism and discipline would guide him in evoking the inner essence of his subjects.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor during World War II, Sato, then in his early 20s, served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, an Army unit comprised of nisei volunteers. His knowledge of Japanese language and calligraphy enabled him to translate and duplicate Japanese maps. After the war, Sato turned to art, beginning formal studies at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, where he was mentored by Ralston Crawford, an influential visiting faculty member known for his work as a Precisionist abstract painter and lithographer. In 1948, he followed Crawford to the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York City, landing squarely in the epicenter of the global art world’s burgeoning modernist movement. At The New School for Social Research in Greenwich Village, Sato found another vital creative mentor in Stuart Davis, a pioneering painter who bridged modernism and pop art.

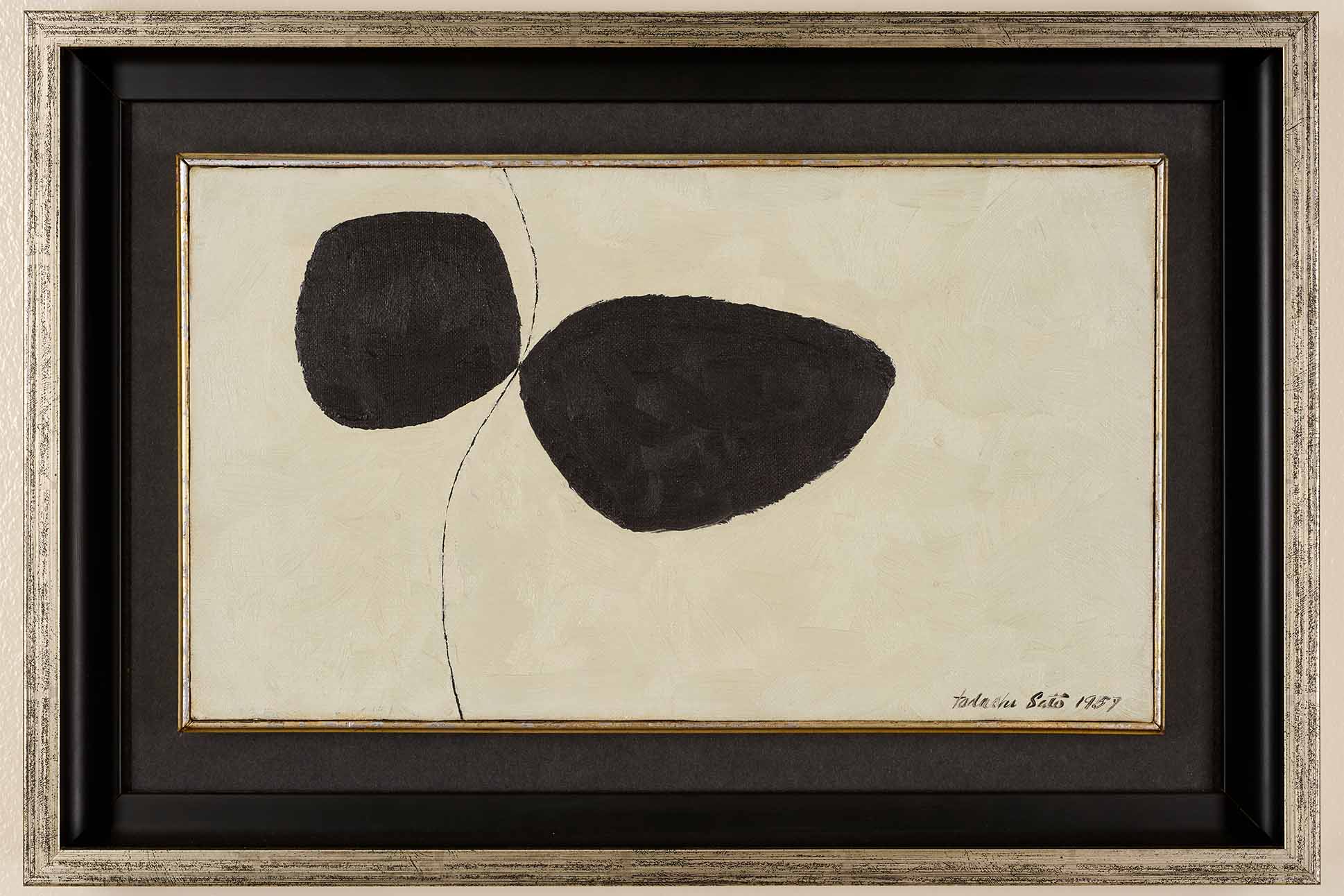

Fascinated by the city’s urban backdrop, Sato began translating its streetscapes into abstract compositions such as his energetic Subway Series, which plays with dynamic shades of black, gray, and white. Making regular visits back to Maui, Sato frequently returned to organic themes that reflected his island upbringing. While many of his contemporaries favored aggressive brushstrokes and bold, high-contrast palettes, Sato’s gentle renderings of lava flows, tide pools, rocks, and seascapes in cool blue-greens and muted earth tones conveyed a sense of serenity. By 1958, Sato had secured his first solo show at the Willard Gallery in Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

“There were many Western-style painters who were painting Hawai‘i themes, like volcanoes and bays, but Sato was doing it in a modern style,” says Maika Pollack, who curated the Tadashi Sato exhibition Atomic Abstraction in the 50th State, 1954–1963, held at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 2022. “Sato was seen by critics of the 1950s as being part of the conversation around avant-garde painting in New York, and he brought that level of dialogue and sophistication to Hawai‘i when he returned.”

In 1960, Sato left New York City’s mercurial art scene for a permanent residence in Maui, where he continued to refine his craft under the guidance of acclaimed artist and printmaker Isami Doi. As his East-meets-West style of abstraction grew more esoteric, Sato’s color palette became increasingly vibrant, incorporating vivid hues of blue, green, rose, and orange. He exhibited artwork alongside fellow Hawai‘i-born nisei abstractionists—Satoru Abe, Bumpei Akaji, Edmund Chung, Tetsuo Ochikubo, Jerry T. Okimoto, and James Park—who formed a collective known as the Metcalf Chateau. This cohort of postwar creatives was instrumental in advancing modernist art in the islands.

In his later years, Sato embraced public installations, making visual art more accessible to kama‘āina, or island residents. One of his most iconic works, Aquarius (1969), graces the floor of the Hawai‘i State Capitol’s open-air rotunda. For the piece, Sato arranged six million Italian glass tiles into a circular mosaic 36 feet in diameter, evoking sea rocks beneath a calm ocean. In 1991, he created another ceramic mosaic, Submerged Rocks and Water Reflections, for the Shinmachi Tsunami Memorial in Hilo, a mural that showcases an interplay of light, shadow, and sea in his signature soft-focus style.

Today, several Tadashi Sato originals are permanently housed at Halekulani, where he once worked part-time before enlisting in the Army. As a successful artist, he later contributed several commissioned pieces. “Tadashi Sato captures the islands’ natural beauty in magnificent abstracted forms, leaving much open to interpretation but clearly showing his love of Hawai‘i,” says Joyce Okano, curator for the Halekulani Gallery exhibit Reflections, which ran from January through June of 2025.

The retrospective showcased five decades of Sato’s artwork, on loan from private collectors in Honolulu, spanning Subway Station #4 (1954) to Spirit of Death Watching (2004). Okano deliberately positioned Spirit of Death Watching as the first piece viewers encountered, noting, “This work deeply exemplifies Sato’s gifts as an artist. Everyone who knew him speaks of his kindness, humility, and deeply positive outlook.”

Painted a year before Sato’s death at age 82, the image depicts the crown of a pink sun resting on the horizon, its yellow reflection floating beneath. Sato signed his name on both the top and bottom of the canvas, leaving the viewer to decide which way is up. “I found myself flipping the painting around, trying to imagine Sato’s perspective,” Okano reflects. “Does the sun set at death—or does death bring the rise of a new life?”