Of all his far-flung forays into experimental sound over the last five decades, Kit Ebersbach believes “the biggest impact I’ve had on this world,” as he puts it, is Aloha ‘Āina: his 12-volume collection of field recordings that finds music in idyllic, undisturbed natural settings across Hawaiʻi.

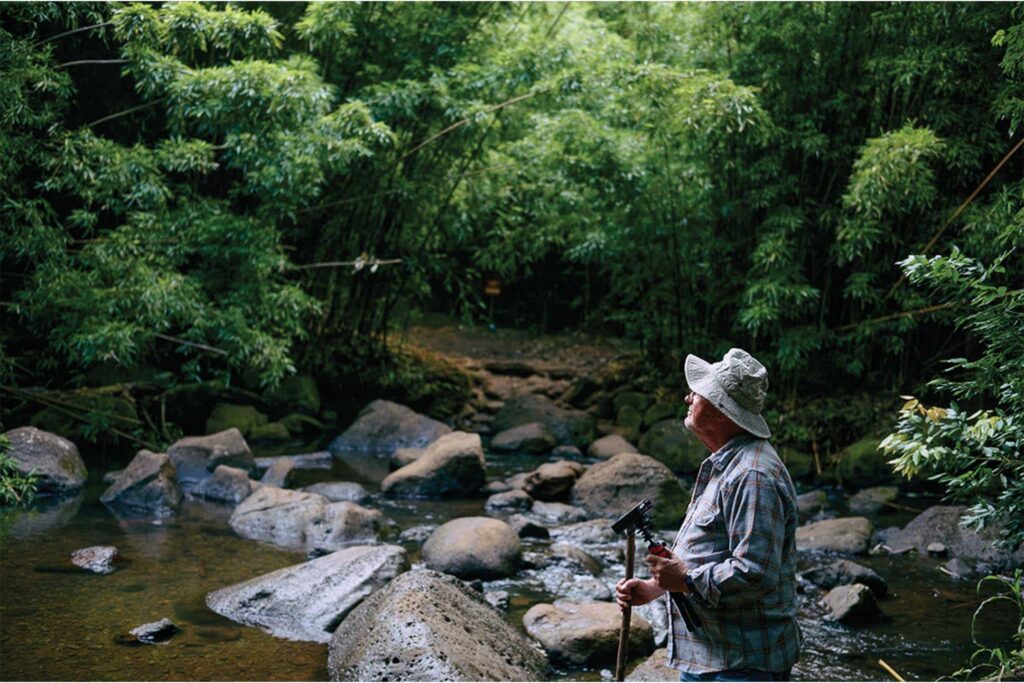

Since the ’90s, armed with his Tascam recorder and his ears as guides, Ebersbach has been venturing into the wilderness and capturing the diverse sounds of Hawaiʻi’s land and waters. On one track, coqui frogs sing an eerie, extraterrestrial chorus in Hilo; on another, falling cave water drip-drops in a syncopated beat on Oʻahu’s Waimalu Trail. Spanning six islands and three decades, Aloha ‘Āina’s 106 recordings form a kind of travelogue and time capsule, with Ebersbach playing the role of sonic naturalist. Not that the 78-year-old sound engineer thinks of himself or his project that way. “I don’t think much when I’m on a trail,” he says. “I just enjoy being on the trail, listening.”

Ebersbach started hiking on Oʻahu in the late ’60s, shortly after graduating from Yale University and moving to the island to pursue a master’s degree in linguistics from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Having grown up in New Jersey, where the freewheeling world of New York City’s jazz scene was just a train ride away, he initially felt “limited” on O‘ahu, alienated from the landscape of adventure and discovery he once knew. Until he started hiking.

“I never got really comfortable here until then,” says Ebersbach, who works out of his recording studio, Pacific Music Productions, in Honolulu’s Chinatown. “And then I realized how big the island is.” He was amazed at how vast the trails were, splintering off into hidden pathways that revealed microclimates and, within those subtle shifts, entirely new sounds.

He dropped out of school after a semester and grew out his hair, devoting his days and nights to playing the keyboard in different lounge acts throughout Waikīkī, then an open-air fantasia for live music. Though he initially set out to be a jazz musician, the exploratory energy fueling then ’70s expanded the scope of Ebersbach’s interests. “It made me curious about everything,” he says.

With curiosity leading the way, Ebersbach hopscotched through a kaleidoscope of sounds throughout the decades, from his jazz-funk lounge act, US, in the ’70s to the neo-exotica of Don Tiki, an ensemble group he fronted in the ’90s. Threading it all together was a kind of Buddhist pursuit: finding the music in everything. “I would buy a [John] Cage record or something, just whatever’s the weirdest record that’s there,” he says, “and I would try to find out what it is that makes it music.”

He started the new wave band The Tourists and Hawai‘i’s first post-punk outfit, The Squids, in the ’70s precisely because of each genre’s “irritating” sound. In the ’80s, he spearheaded the avant-garde performance art group Gain Dangerous Visions, which he describes as “a bunch of kids who weren’t necessarily musicians, but they all wanted to do things.”

I never got really comfortable here until I started hiking. And then I realized how big the island is.

Kit Ebersbach, Musician

That ethos animates Aloha ‘Āina, presenting nature as a kind of ever-evolving symphony. Each of the 12 volumes runs an hour long, with tracks ranging from a little over a minute (“Palms, Kamoamoa, Hawai‘i Island”) to nearly 16 minutes (“Near the Mauka Junction of Pauoa Loop Trail, O‘ahu”) depending on how long the subject matter sustained Ebersbach’s interest. “After eight minutes of a rushing stream,” he says, “it gets to be like, OK, that’s nice, now let’s get on to the birds or something.” (Bird song dominates the collection.)

He makes every effort to avoid noise pollution—an ambitious feat on Oʻahu’s crowded trails and beaches—preferring to present a romanticized version of Hawaiʻi instead. This often means venturing off the beaten path and stepping away from the recorder to avoid attracting flies or capturing the sound of his own breathing.

Part of Aloha ‘Āina’s impact has to do with the timing of its launch in 2020. Roger Bong, owner of the Honolulu-based record label Aloha Got Soul, approached Ebersbach about his field recordings just as COVID-19 lockdowns were underway. “We have this treasure trove of what could potentially be very healing, therapeutic, inspiring sounds for people, from a place that’s very special,” Bong reasoned. “And it could reach people around the world in a time when everyone’s stuck at home.”

Bong first encountered Ebersbach’s field recordings years earlier on a flight operated by Hawaiian Airlines, where Ebersbach has been curating the in-flight radio channels for over a decade. A selection of Ebersbach’s recordings live on an ambient channel called Environmental Journey. “I would fall asleep to the channel, wake up to sounds of the bubbling stream, and then fall back asleep,” Bong says. “Yeah, I was a fan.”

Though Ebersbach and Bong have achieved their goal of releasing 12 volumes of Aloha ‘Āina, Ebersbach still heads into the trails and takes field recordings when he can, finding solace in Hawai‘i’s great expanses and in the sense of connection that once eluded him. “My friend’s father, who’s an evangelical Hawaiian minister, says ‘The trails are your church,’” Ebersbach says. “And yes, it was true.”