There are still some things sculptor Jerry Vasconcellos doesn’t know at 75: what he’s making when he sets out to carve the many wood and stone figures perched throughout his carport studio; what sometimes slows him to a halt, forcing him to go start something new; what will happen to all his unfinished works when he dies.

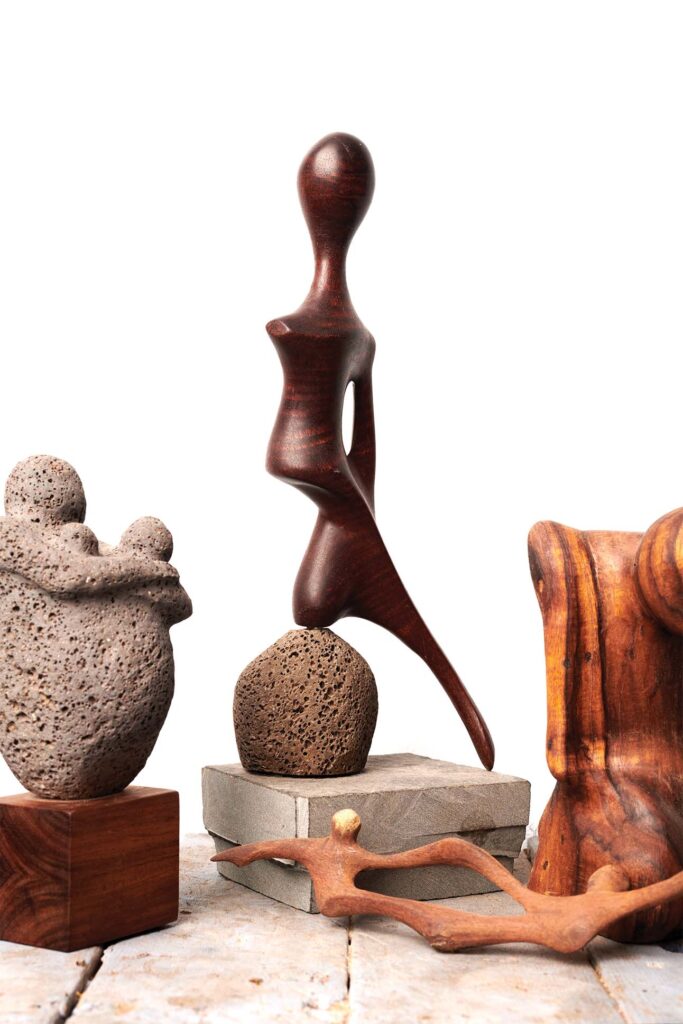

On a rainy winter day, Vasconcellos fishes out a black stone from a pile of uncut shapes on his desk. “It’s more fun for me to try and figure out what the story of a piece is as I’m doing it,” he says. He plugs in a Dremel power tool, flicks on an old fan, and gets to work, dust blowing as he grinds a small valley between two knobs in the rock. “Hopefully the visual will be powerful enough that someone else can see that same thing,” he says, “or they see what they want to see.”

Blue-eyed and clean-shaven but for a stout gray mustache, he’s wearing an aloha shirt and board shorts, elbows resting on his knees as he sits and carves. “What I’m trying to do is to work towards a reason for doing it,” he says. Vasconcellos has been what he calls an “instinctual” sculptor most of his life. His works draw out the natural curves of the materials he forages from the beach and in the woods.

He spent most of his life in Honolulu before moving north several years ago to the tiny town of Hau‘ula, where he lives a short walk from the shore. “This just swallowed me. I don’t need anything else,” Vasconcellos says, content just to sell enough work to afford a nice dinner with his wife now and again. “So much of what I’m doing is for myself.”

Vasconcellos grew up in the storied Wailele artist colony, built alongside a waterfall deep in verdant Kalihi Valley. Soon after his family moved in, the top floor of the house burned down, so they moved into the gallery, living among the art of former residents Lillie Hart Gay and George Burroughs Torrey. As a teenager, he plunged to the bottom of the river by his home and emerged with a dark, porous rock. At the time, he’d been taking in the quasi-abstract figures of Henry Moore and Jean Arp, so he took a hammer to the rock and pounded out a donut shape. Afterward, he asked himself: “Did it look like more than a rock with a hole in it?” He carved another rock, then another. The aim: “Create that which wasn’t before.”

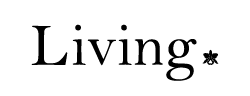

After college at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Vasconcellos found a job that allowed him time for art. As an ocean recreation specialist for the City and County of Honolulu, he ran body-surfing contests and other ocean-going programs while honing his artistic eye for foraged materials. He scrutinized beaches for stones, looking for “a quality rock” with an “appropriate shape.” He’s found rarities like feather-like lava rock and dense red lava rock conjoined by a crystalline layer. The material’s consistency is key, he says: “You need to know that you can carve it.” He used to hike up into the mountains looming over Honolulu to look for wood that needed to “be released.” He’d start carving a piece on site before carrying it down from the woods to complete it. Finding materials in the wild was both cost effective and enlightening. He grew to notice certain details as he carved, like “the response to your impositions” in the wood. Vasconcellos doesn’t force the material to bend to his will, instead allowing subtle forms to reveal themselves: an almost-head, an almost-face, an almost-dancer.

Vasconcellos doesn’t force the material to bend to his will, instead allowing subtle forms to reveal themselves.

In the late 1970s, Vasconcellos went to an art show by Rocky Jensen, who ushered in the contemporary maoli fine arts movement and founded the group Hale Nauā III to promote Hawaiian culture. “I was just taken by the whole thing,” Vasconcellos says. “He let me join as a non-Hawaiian.” Vasconcellos started showing his art with the group, and Jensen passed some of his knowledge of Hawaiian culture to him. “My knowledge of things, locally, was missing,” he says.

Vasconcellos credits Mau Piailug, the Micronesian navigator who piloted the Hōkūle‘a on her maiden voyage from Hawai‘i to Tahiti, with teaching him how to carve. He was working his county job at Kualoa Park in 1976 when Piailug showed up there to put the canoe together. Vasconcellos made himself a devoted acolyte. “As far as I was concerned, it was a total apprenticeship, and as far as he was concerned, I was there helping him,” he says. Piailug taught him to understand his materials, use an adze, and always work with the grain. Vasconcellos’ tools of choice are still chisels and adzes he made himself, which he packs in two canvas bags and takes to a park near his home to work on pieces.

Vasconcellos demurs about his success as an artist. Decades ago, his first solo show, Who Would Have Thought a Dead Tree Could Talk?, sold just two pieces. “It was all very slow. I’m not even clear on what renown I have,” he says. “I’d get mentioned in the newspaper when I was doing shows with other groups, and that was always nice.” Today he sells pieces at Nā Mea Hawai‘i and Cedar Street Galleries in Honolulu. His past public commissions include a congregation of stone figures outside the Keahuolū Courthouse in Kailua-Kona and, flanking the pedestrian path at the University of Hawai‘i Cancer Center, a pair of totemic sculptures with carvings that resemble watchful eyes.

In his studio, Vasconcellos continues grinding away, undisturbed by all the dust flying from the stone he’s working on as he turns it over in his bare hands. Out in the yard, dozens of stones sit untouched “because I like ’em so much,” Vasconcellos says, admitting he may never carve them into sculptures. Others have been shaped into graceful, undulating forms. Tall ones stand along the wall with an almost human presence. One stout wooden figure vaguely resembles a tiki statue. And on one rough and knobby hunk of wood, he’s penciled out possible contour lines. “As something starts to develop, you pursue that and deal with it however you have to,” he says. “It’s nice: The more you do it, the more you feel you can do it.”