“We all look to the past and to the future to find ourselves,” wrote the late artist Isamu Noguchi. “Here, we find a hint that awakens us; there, a path that someone like us once walked.” It’s a quote returned to often by musician and composer Leilehua Lanzilotti, who grew up frequenting the same path Noguchi tread to construct his sculpture “Sky Gate” near Honolulu Hale, where Lanzilotti’s father worked for then-Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi.

This was long before she was formally introduced to the work of the prolific American sculptor, and just one of her formative experiences encountering art in outdoor spaces. Lanzilotti’s mother, who worked at the former Contemporary Museum of Honolulu, encouraged her to explore the museum’s fields and gardens, which were adorned with kinetic sculptures. “I loved being outdoors in the middle of all that art,” she recalls. “It was really influential to my way of thinking about art and music-making in a playful way.”

But the kind of mastery that Lanzilotti is known for also required structure. As a child she began studying under Hiroko Primrose, a “strict, old-school, and incredible” violin teacher, while also dancing in Hālau Hula O Maʻiki, an experience that provided her with an in-depth cultural education in Hawaiian language and music.

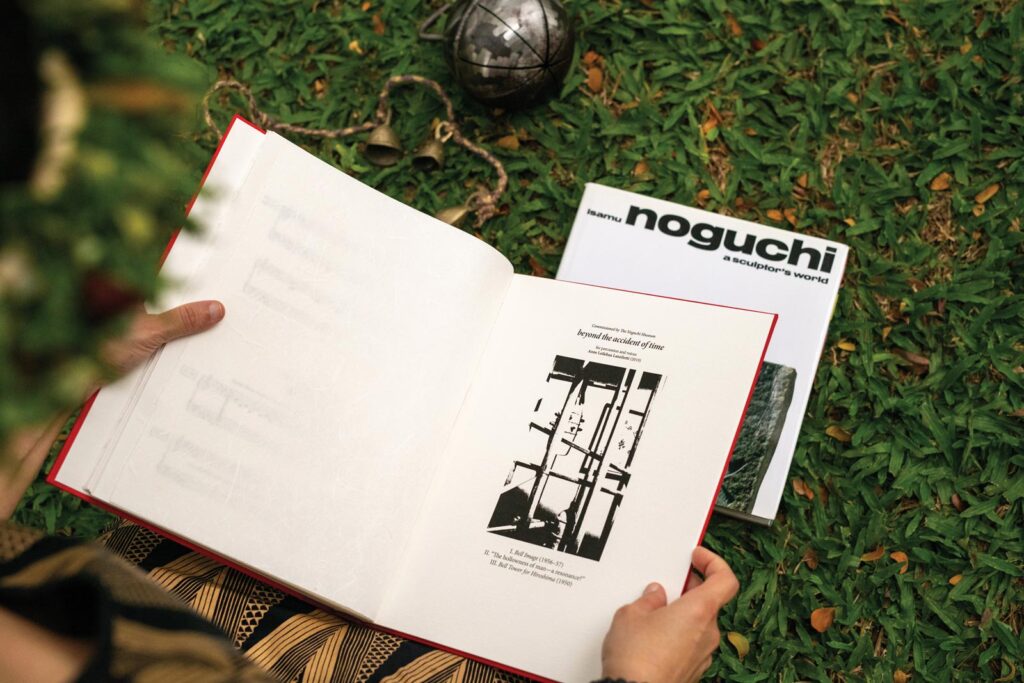

After graduating from Punahou School in 2002, she spent the next 19 years learning, playing, and teaching music across the United States and Europe. While living in New York, she began collaborating with The Noguchi Museum in Long Island, an institution dedicated to the work of Isamu Noguchi. Inspired by the museum’s collection, she proposed putting on a performance in the space.

The museum liked the idea and invited her to play something for an upcoming exhibit featuring two Noguchi sculptures that had never been displayed together before: “Birth,” a travertine figure of a woman with her head thrown back, and “Death,” a metal figure being lynched. The museum offered her two obsidian sound sculptures that Noguchi made to be played as instruments, suggesting that she ring them at the start of her string and vocal performance. Instead, Lanzilotti created an entirely new work that incorporated the sound sculptures throughout the composition.

The project kicked off an ongoing collaboration that continued even after Lanzilotti moved back to Hawai‘i in 2021. Currently, she’s finalizing a composition for “Sky Gate,” a fitting project for her return home. When she was at The Noguchi Museum, she saw a miniature model of “Sky Gate,” and while it looked familiar, it wasn’t until later that she recognized it as the same sculpture she and her dad would eat lunch under when she was younger.

Mysterious and imposing, the sculpture’s painted steel frame holds an undulating ring 24 feet in the air above a circular concrete platform. The public artwork was part of Fasi’s efforts to beautify the Capitol District, though it wasn’t well received at first. “There are a lot of funny articles from the time that are like, ‘What is this thing?’ Lots of people hated it,” Lanzilotti explains, adding that perceptions have changed given how the sculpture interacts with the park today. “The way the trees have grown in, the way the branches reach out and mirror the tetrahedron shape. It’s like Noguchi was making this sculpture for now, almost 50 years later, for a version of the park he’d never see.”

Lanzilotti’s performance, written for ten musicians, is a fulfillment of Noguchi’s original vision to activate the park as a community space. “He wanted concerts here,” Lanzilotti says. “Depending on which musician you’re close to, you’ll hear different things. That’s different from being in a concert hall, where you don’t move. This project is about the relationship between people and art and parks. It’s about being in the world.”

In many ways, Lanzilotti is collaborating with Noguchi himself, even though he worked in a completely different artistic medium and died in 1988, when Lanzilotti was five years old. But the art he left behind has resonated with her, specifically Noguchi’s approach to his creative practice.

A lot of contemporary art is about practicing “perspective-taking,” or the act of perceiving a situation from alternative points of view, Lanzilotti says. “It’s interesting to see how Noguchi approached the parameters of a park or a material, engaging with his work and walking around it, looking at it from different perspectives, and trying to understand why he would do that, or what his approach was,” she adds. “Creativity is problem solving.”

Explained further, perspective-taking is an act of empathy, one of the most potent problem-solving tools we have. “It’s hard for people to hear each other and see each other’s perspectives,” Lanzilotti says. “But contemporary art can help bring communities together. It can be a way to understand each other.”