Distinguished by their conical shell shapes, ‘opihi (limpets or sea snails) line the shorelines of the Hawaiian Islands, dotting large rocks or boulders singularly or in clusters where the ocean is rough and algae is plentiful. Braving the pounding surf and slippery rocks, ‘opihi pickers risk their lives to ku‘i ‘opihi, or pry the limpets loose from a rock with a knife. “He i‘a make ka ‘opihi,” as one Hawaiian proverb goes, “the ‘opihi is a fish of death”—a reference to the danger of being washed away by the waves. ‘Opihi pickers have long learned never to turn their back on the ocean, but one missed wave could mean the difference between life or death.

“‘Opihi are a culturally revered and important species, not just for their ecology, but also as a food species and [for practical use],” says Anthony Mau, who holds a doctorate in molecular biosciences and bioengineering and studied tropical limpet species.

In traditional Hawai‘i, ‘opihi was part of the Native Hawaiian diet starting at infancy. A little past six months old, a child would be given the soft parts of ‘opihi with some poi or sweet potatoes, scholar Margaret Titcomb wrote in the research paper “Native Use of Marine Invertebrates in Old Hawaii.”

“Even in 1969, ‘opihi were an important part of the diet of most of the Hawaiian families living near the shore,” Titcomb continues. “The favorite method of preparation was raw and salted, either with or without seaweed. They were sometimes washed clean and then cooked in the shell, in a calabash with hot stones. The shells were picked out later. This method enabled the delicious liquor (kai) to be saved.”

The kai was fed to the sick and young, and small, bitter ‘opihi were used in healing and sorcery. The leftover hard shells were sometimes used as jewelry, but mostly as tools. Their sharp edges were used to scrape and scoop or peel things such as the inside of a coconut or the outside of raw taro.

In Hawai‘i, there are three common types of ‘opihi. The ʻālinalina (yellow-footed limpet) is a favorite but located where the waves are the roughest. The kōʻele (limpet with highly pointed shell) is very large, and thus coveted, but its meat is tougher than others and it’s found underwater. The makaiaūli (dark-footed limpet) lives higher on the rocks than the ‘ālinalina and so are easier to harvest. “The ‘opihi was a favorite food source for Hawaiians,” says Marques Marzan, cultural advisor at Bishop Museum. “Everyone had their own preference on which ones they like to eat.”

Following Western contact, ‘opihi populations declined dramatically since the early 20th century, especially on the island of O‘ahu. The threat to ‘opihi has mostly been blamed on overharvesting, but there are other contributing factors, including a changing shoreline landscape due to development and pollution that impacts food that ‘opihi eat, such as algae.

Mau’s findings refute the overharvesting argument. As a doctoral student, Mau researched aquaculture technology for ‘opihi at the University of Hawai‘i, where ‘opihi behavior can be studied in a way that can’t be done in the wild: “There are certain areas that naturally should have less ‘opihi than others, and there are certain conditions that allow for ‘opihi to thrive and to be abundant versus others that don’t.”

To manage overharvesting, state law produced in the late 1970s prohibits picking ‘opihi with shells that measure less than 1.25 inches in diameter and selling ‘opihi meat (without the shell) that measures less than half an inch. Mau and other researchers, however, think the law should change now that there’s more information on how long they live, how fast they grow, and when they reproduce, whether by age or season.

The ongoing examination of the life cycles of ‘opihi, and potential changes to the law based on new research, could mean a better supply of ‘opihi in the future. “We’re trying to enhance reproductive success but also be able to harvest as much as we can outside of those windows, because restoring the populations of ‘opihi doesn’t do us any good if we’re not eating them,” Mau says. “It’s not a resource if you can’t use it.”

In traditional Hawai‘i, ‘opihi was an important part of the Native Hawaiian diet starting at infancy.

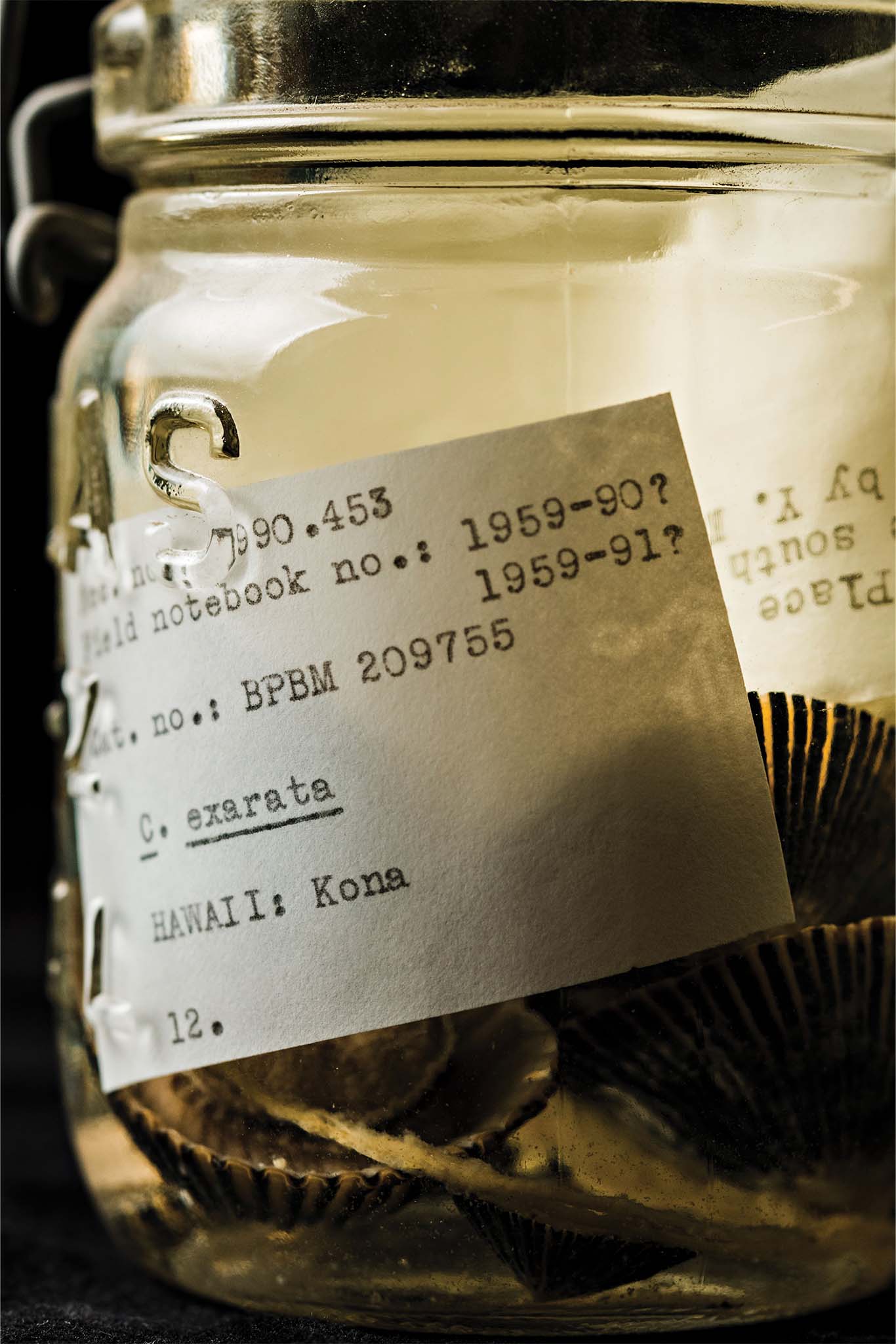

There are three common species of ‘opihi found in Hawai‘i that are endemic to the islands.

Renowned modernist architect Vladimir Ossipoff picks ‘opihi on Kaua‘i in the 1970s or ’80s.

In Christian Edwards’ artwork ‘Opihi Village (2019), on view in the lobby of Halepuna Waikiki, ‘opihi are rendered in hand-built, high-fired stoneware and iron and cobalt oxides.